Part 11 of my personal magic carpet-ride through Persia.

Containing mostly carrots but also cardamom, rose water, saffron and surprisingly little sugar, moraba havij, when spread liberally on a hot naan, was a goddess amongst jams. As my penultimate Iranian breakfast vanished like a rat up a qanat, I could think of no better way to start a day

The mere thought of the morning naan was usually enough to make me leap out of bed as soon as I had woken up. It always came to the table steaming hot and deliciously charred. How would I cope without such dawn delicacies when I got home? A bowl of Frosties was no match for this. The only place I could recall naans being served in Chippenham was the Taj Mahal on the Causeway but they never opened before noon. Apparently there was a Taj Mahal in India too. What a coincidence!

My only concern about the Persian carrot jam was that if it caught on there might be a succession of sweet preserves made from other vegetables, and with the threat of Brussels sprout jam lurking menacingly on the breakfast table it was likely that a fair proportion of the world’s population would be afraid to emerge each day from underneath their duvets.

As we were coming towards the end of our holiday, Mahtab handed out X Travels customer satisfaction questionnaires and asked us to start thinking about what we would write on them. She reminded us that because we were in the Islamic Republic of Iran it was forbidden to write anything uncomplimentary about the travel guide lady, especially her fondness for breakfast naans and jam. Scanning through the sheet I thought that it all seemed quite straightforward until I came to the ‘Mosque of the Trip’ section. There had been so many. Some people started scribbling on theirs straight away but Mahtab snapped at them, suggesting that they should carefully consider their answers but shouldn’t write any of them down yet as we still had some travelling to do and no one could ever tell when there might be another mosque just around the corner. I panicked because I couldn’t remember the name of the one in Na’in that had no iwan (vaulted portal). I felt like I was sitting a GCE ‘O’ Level Islam exam and I wasn’t wearing my lucky underpants.

Being reunited with the bus meant being reunited with Volvo Vahid, which was great, but he couldn’t remember the name of the mosque in Na’in either. It also meant that the day would involve a bit more driving around than the previous one had done. The Jameh Mosque (or Friday Mosque) was only two kilometres from the hotel so we could have walked it in thirty minutes, plus the other five or six hours that we would have required to stop to answer the local people’s questions about our lives at home and the beautiful clothes that we wore whilst out fox-hunting and how many times we had met James Bond. So we obediently hopped on the bus.

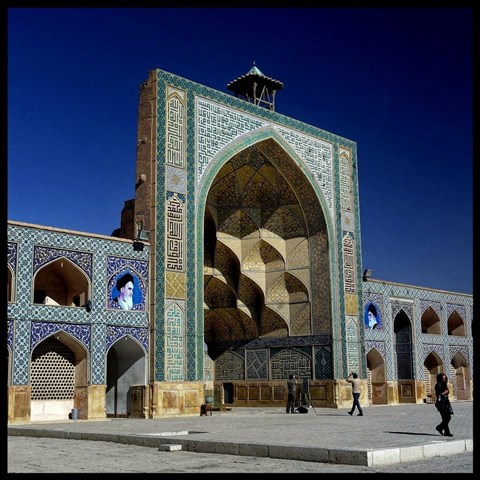

At the end of the short journey, before we had even hopped off the bus, the Jameh Mosque wowed me like only a few buildings in the world had ever done before. In the months leading up to the start of the trip I had worried that I’d get bored of visiting so many mosques. Wasn’t one mosque just the same as any other mosque? But I came to realise that they each had their own distinguishing features and despite the fact that all previous mosques visited since my arrival in Iran had been places of great interest and incredible beauty, I could safely say that Isfahan’s Jameh Mosque outshone them all, and why.

The whole building, with its four contrasting iwans and magnificent ablutions fountain in the centre of a great courtyard, was utterly stunning. What made visiting this place an even more unbelievable experience was the fact that the north and south iwans had been built as long ago as the eleventh century. There had been a mosque on the site since 771 AD and in its current form it was a UNESCO World Heritage Site considered to be one of Islamic architecture’s biggest and most important monuments in Iran.

In such a gorgeous setting it was just about impossible to take a bad photograph, though because of the presence of shadows on such a sunny day and the lack of an ultra-wide wide-angle lens, it was difficult to capture more than one iwan at a time. The enormous rooks flying around their minaret roosting places made it even more photogenic and the absence of other tourists was an added bonus that I enjoyed here just as I had at most of the other historic sites we had visited.

The frescos on the interior of the Vank Cathedral, or Holy Saviour Cathedral, in the Armenian quarter of the city were superior to any that I had ever seen before, particularly the one depicting Heaven, Earth and Hell in three horizontal layers. The Hell bit looked even more sinister than I had ever imagined Hell to be. Other members of the group who had visited the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City (I hadn’t then but I have since) said that the painting that decorated the ceiling of the cathedral was at least as good as the work of Michelangelo; but the world didn’t know about this phenomenal treasure because the world was so reluctant to visit Iran.

I was disappointed that photography wasn’t permitted and there was no sign of postcards for sale in the cathedral shop. On the way out I discovered that video recording was permitted provided that an official permit had been purchased from the shop beforehand. Had I known, that would have been perfect. I could have captured a permanent record of damned and tormented sodomites with blood squirting from their bottoms to make my holiday complete. In a frame, such a picture would have been the ideal gift to adorn my mother’s mantelpiece. But to find this out after the event only added to the frustration.

From the outside, this Christian cathedral didn’t look very interesting and was nowhere near as ornate as its Islamic neighbours. Apparently it had been established in the early seventeenth century by the hundreds of thousands of Armenians who had been forced into an enclave by Shah Abbas the Great as part of his scorched-earth policy in Armenia during the Ottoman War of 1603-1618.

I was unaware of this at the time but, whilst doing a little research recently to check the accuracy of my writing, I discovered that Isfahan’s Christian Armenian quarter was the only place in the whole of Iran where it was legal to buy and sell alcohol. We must have walked past bars that we didn’t know about. Thirteen years after the event I discovered that we could have gone and had a pint. So, to make up for lost time, that’s where I’ll be having my stag party when I get married.

Next on the day’s busy itinerary was a visit to three beautiful old Isfahani bridges which spanned the broad majestic patch of baked mud where the Zayandeh River used to flow before it was redirected to supply a series of reservoirs many kilometres away. They were impressive structures even without there being water flowing beneath them but, from photographs that I’ve seen taken in the recent past, they had been a spectacular way to cross a great body of water. Ever optimistic, I hired a pedalo and sat in it, waiting for the tide to come in… but it didn’t, and still hasn’t.

That day being the Moslem Sabbath, everyone in Isfahan (including the Armenians) was off work and had gathered in the parks on the banks of the meandering sun-parched mud. Kids enjoyed the thrill of paddling without having to remove their shoes and socks. The parks, however, were very green and flowery and everywhere I looked there were people having picnics, flying kites or just enjoying the searing autumn sunshine. There was such a lovely, happy, fun-filled atmosphere despite there being no alcohol, or perhaps because there was no alcohol.

Lunch today took place at the famous Abassi Hotel, near to the shop where I had bought my CDs of traditional Persian music a day earlier. Knowing the way there made me feel like a local and impressed fellow group members (or maybe encouraged sarcastic ribaldry) as we approached on foot along the tree-lined boulevard from where Vahid slept in his bus. When I had seen it the day before I wasn’t aware of the importance of this old building that Mahtab was able to explain as having been built in the eighteenth century by Sultan Husayn of Safavid as a caravanserai (a place to provide food and lodging for travellers along with their camels or horses). Although it contained a lot of Middle Eastern art and antique furnishings that created a feel of majestic splendour, it took time to imagine how it would have originally looked as a lot of steel and glass had been added in the refurbishment process.

I was also impressed by the majestic splendour of the spiced chicken sandwich that I had, but maybe not by the ice tea which was really just cold tea in a taller than usual glass. Such was the level of the hotel’s opulence that it had often been chosen to accommodate leaders of the nations of the OPEC cartel (Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) as they manipulated global economics with their fluctuating price for a barrel of crude.

I hadn’t, at any point of our Persian adventure, seen any reason to dislike any of the members of our group and by this point we seemed to have all bonded superbly, and Mahtab our wonderful guide too. It seemed strange to sit around and chat in the lounge of a luxury hotel, feeling more like old friends than a group of recently acquainted travelling companions. In my life I have noticed that nothing has brought people close together as quickly as sharing the experiences of being thrust into unusual situations whilst far from home. This had been a lunch of great style and hilarity that I would always remember. Iran was unique but so were the members of our group, and one without the other just wouldn’t have seemed right.

I bought some postcards in the hotel’s gift shop, not to send but to keep. I often do this as photographs aren’t always possible. I paste them into my journal. Some of the cards on sale were pictures of ancient Persian art. One of these depicted a Moslem lady posing topless. She was pouting for the camera too! I was shocked but I had to buy it. I showed it to Oldham Liz and, like two children, we giggled together. I went to the cash desk to pay, handing it over to a very attractive, very sophisticated looking and well spoken Moslem lady shop assistant. Suddenly I felt very embarrassed. Even though the picture must have been painted hundreds of years before and was really quite innocent, under the circumstances I felt like a dirty old man buying pornography from the top shelf of a grubby little newsagent’s shop. It was an Islamic custom for a man to not make eye contact with a woman so, by adhering to the ways of my hosts, I managed to survive the sordid experience.

Thinking that I had averted disaster, I was dismayed when Oldham Liz immediately ran out into the lush and bounteous hotel garden to tell everyone in our group about what I had done. So lovely ladies, particularly Oxford Ann and Mahtab with whom I would never have dreamt of discussing anything rude, suddenly wanted to peruse my purchases. My reputation was in tatters but everyone else was in fits of laughter.

Our tour of Isfahan, a city with which I had fallen in love, was drawing to a close. All that remained was a drive out to another ancient Zoroastrian fire temple on the outskirts. Typically, it was built on a rocky outcrop which appeared easy enough to climb as ladies in sandals and chadors were scaling it but, despite talk of a fantastic view from the top, we had to give it a miss because we were booked in for the four o’clock showing at the nearby Shaking Minarets.

Some might have found the Shaking Minarets a bit disappointing but I loved them. They formed part of the fourteenth century tomb complex of Abu Abdullah. On arrival we were directed to stand on a small lawn beneath two old but fairly small mud-built minarets. We stared in gleeful anticipation for ten minutes, expecting them to start their trembling in some mystical manner but nothing happened. And then, bang on the stroke of four o’clock, a fat Iranian bloke climbed a ladder and manoeuvred himself a little dangerously to the top of one of the towers. He then proceeded to shake his huge arse and belly about so vigorously that both minarets began to shake too. Some of our party had expected something a bit more spiritual but for me it had been wonderfully unique and memorable just the way it was.

Shaken but not stirred, we were delivered by Vahid and the Volvo back to the square in the city centre and in ones, twos and threes, our group split up again to do their own thing. My thing was to buy a saffron ice cream and to make another attempt at recording the maghrib azan (sunset call to prayer) from the Shah Mosque on my phone. Three or four seconds after I pressed the phone’s red ‘record’ button, my favourite postcard salesman arrived. This man, always courteous and smiling had been trying to sell me some of his fine wares for a couple of days but I had always put him off by saying that I had to dash away to keep up with the rest of the group, which was perfectly true. On this occasion there was no group so I couldn’t say no. Each time we had met and quickly parted I had promised him that I would buy some cards as soon as Mahtab gave us some time off. I had genuinely wanted some so I wasn’t just fobbing him off, although I was sure that he suspected that I was. So with him lusting over my by now quite thin wad of rials I had to quickly complete the deal and start my recording again when the second round of the muezzin’s call started. This was my final chance so I had to get it right. I was relieved when at last I was able to play back my phonographic masterpiece, discovering that it contained additional material in the form of the sound of the bells that jangled on the horsedrawn carts that hauled passengers around the square for pleasure. But at least the horses didn’t speak or try to sell me anything, so I considered the session to have been a success.

The square after sunset was sight to behold. With the outline of the Shah Mosque silhouetted against the vivid orange sunset, the eerie sound of the azan, the chatter of Iranian passers-by, the fountains sparkling in the beams of strategically placed floodlights, and the mouth watering smell of the Isfahani street food cooking in kiosks on every corner, I cherished every second that I had spent sitting there alone and taking it all in. Then I heaved a sigh and said goodbye to dear old Naqsh-e Jahan.

Arriving back at the hotel I found some of our group drinking coffee in the lounge. Mahtab was with them. There was an unusually sombre mood. Apparently earlier that day Libyan leader, Colonel Gadaffi had been shot dead near his home town of Sirte. The whole world, according to the BBC, seemed to be excited about this and although he had been a cruel dictator I couldn’t join in the jubilation as I considered the current situation in Iran and wondered what might happen next in the Middle East. The political state of the whole region seemed so volatile and it was heart-breaking to think about the effect that it might have on the lovely people I had met in Iran.

Mahtab, although having said that she detested the man, sounded quite morose. She told us that a group of Americans that she was supposed to be guiding along the same itinerary as ours the following week had suddenly cancelled their trip because they were worried about an outbreak of civil war in Libya. This, she said, was a strange notion as Tehran was approximately 4,500 kilometres from Tripoli, the Libyan capital; a distance almost exactly the same as the entire width of the USA at its widest point. The prospect of ten days without work or pay was playing on her mind much more than political instability was.

After everyone else had gone to bed I too went up to my room. Suddenly the atmosphere in the Setareh Hotel didn’t seem so jolly. I thought about having a bottle of beer to cheer myself up. I opened the door of the minibar to find there was just one left. It was alcohol-free carrot beer… my favourite!

Photograph: One of the four iwans of the Jameh Mosque in Isfahan.

Link to Part 12:

Cherries and Dahlia Petals