This Sort of Thing - June 2024

Hundred Word Poem

Six decades flew past but no pen touched my page

Never pausing to note how a world ran rampage

Looking on from my perch in a writer’s gilt cage

People and places, the most precious of times

Once juicy and ripe for telling stories and rhymes

Fade little by little each time the clock chimes

Tides turned while candles burned

Mistakes all made and lessons learned

There’s calmness now, a life’s upturned

My glass half full, maybe more, two thirds

I sit alone amongst trees. As the songs of wild birds

Harmonise with my thoughts, I write today’s hundred words

1 June, Saturday

Summertime and the living is easy, unless you’re trying to park your car in tourist-swamped Arbanasi. Why do they visit our local haunts when there’s so much more to see in Rome or Barcelona or Alton Towers? Gorna Oryahovitsa has never been a holiday hotspot so we had a pleasurable time there instead with vitamina salata and freshly baked garlic parlenka. It was, however, very hot and the waitress did have spots.

The evening’s Gypsy music from up the hill seemed mournful. It was International Children’s Day. Perhaps the parents resented having to make something special for their kids’ tea.

2 June, Sunday

Our Italian trip sadly abandoned, the self-compensatory days out scheme is also foundering. We've been tryin' for Troyan for a week but mountains are best avoided when there's electric rain and herculean hailstones. Thankfully our covered terrace is the new holiday haven. It's like being on a real holiday but without any danger of having to talk to people over breakfast.

Only our shouting 'Fuck off mosquito!' at twenty-second intervals breaks the silence. My flesh, having marinated in garlic and red wine for decades, is understandably irresistible to the vampiric little gitbags whose voracious appetites put Vlad Dracul to shame.

3 June, Monday

Our lifestyle is not completely problem-free. Breakfast conversation centred on a drooping caesalpinia gilliesii, a legacy of our 2020 Mexican backpacking tour. Seeds we found in public gardens in the mountain town of San Cristóbal de las Casas (Spanish for grotty hostel with shit breakfast) when planted in Malki Chiflik flourished into a beautiful Bird of Paradise of the Desert Tree. But lately she’s distressed.

‘Lift it, shift it!’ is the rule for struggling plants. Whilst digging a new hole in the new territory for dear niña, I experienced temperatures greater than in El Desierto de Sonora (even worse breakfasts).

4 June, Tuesday

Our felonious felines partake in organised crime, the subject of each day’s carnage determined by this schedule:

Monday: blackbird

Tuesday: lizard

Wednesday: slow worm

Thursday: shrike

Friday: man-eating grasshopper

Saturday: snake

Sunday: rat

Occasionally, when they’re feeling extra generous / vicious, we’re treated to extra helpings, and we always get a rat on Sundays as if it was some sort of luxury.

Usually carcasses are deposited by the back door but sometimes cross into the kitchen. We have a dedicated dustpan and brush for hurling them over the garden wall into the forest which now resembles a Flanders War Cemetery.

5 June, Wednesday

For our terrace we procured an ultraviolet device with a sticker stating This machine kills insects! Woody Guthrie would have been proud.

Stingers, biters and flappers don’t stand a chance but tough little ants love it. Perhaps recognising the device is Swiss-made they are in attendance to assist with the suicides of hexapod invertebrates. But they clog up the works. Only the Hoover’s blow setting can unclog the cloggage and restore a state of non-scratchy normality as we sip our Rodopi chai at sunset.

I can’t dispute its ultraviolet properties. It reminds me of Bailey’s nightclub in Sheffield in 1976.

6 June, Thursday

Continuing our Italian holiday at home adventure, Priyatelkata, brandishing her shiny metal device with polished wood operating handle and singing ‘I’ve got a pasta machine’ in the style of rock band Hawkwind, knocked up a bit of homemade squid ink tagliatelle (мастило от калмари, pronounced ‘ma-stee-loh ot kal-mah-ree’). A delicious accompaniment to our fresh salmon baked with locally grown vegetables, even though during the two hours that it had hung to dry from a pole between two kitchen chairs it had looked a lot like the dogs’ towel.

She had followed a generations-old family recipe from Apulia… corde dei cani bagnati dal mare.

7 June, Friday

Combining my technical and linguistic skills, I helped a bewildered Bulgarian lady at Kaufland’s self-check-out Big Brother contraption.

Meanwhile my spectacles were in their case sandwiched between two Cornish Mivvies in the car boot; an environment I imagined colder than Suella Braverman’s heart. But penetrative Balkan sunshine heated them such that I suffered third-degree burns to nose and ears.

To maintain our Italian theme, I bought apfelstrudel. Well it’s an Austrian delicacy and Austria’s beside Switzerland where 8.2% of the population speak Italian. It’s lush with a clod of heavy duty yoghurt. Apparently Gina Lollobrigida couldn’t get enough of it.

8 June, Saturday

In a dusty old book of Bulgarian folklore tales, I read this:

One day long ago in a village near Sliven, Hitar Petar met his mean neighbour, Nastradin Hodja by the fountain. Knowing that Petar was a funny man, Nastradin Hodja asked him to tell a joke.

‘Easy! Just wait here while I go home to get my big sack of jokes’ said Hitar Petar.

Nastradin Hodja waited where he stood for many hours before eventually realising that he was part of the joke.

Hitar Petar went on to become a bus driver on the number sixteen route in Leeds.

9 June, Sunday

Election day so there’s no alcohol on sale in shops, bars etc. because we need to be sensible. Administrators always overlook the fact that every Bulgarian house has 100 litres of homemade rakia stored in the ironing board cupboard. Priyatelkata and I aren’t eligible to vote, probably because we don’t drink or own an ironing board.

Turning on the air-conditioning in June is like turning on the heating in October. Too early! Two months hence, as the sun melts the steel plate in my head, we won’t feel the benefit. But our house littered with wilting bodies made it unavoidable.

10 June, Monday

Boyko Borissov, it seems, will become our new Prime Minister… again! Good news in that having been Prime Minister three times before he’s the only Bulgarian politician whose name I can remember.

Long ago, Boyko was bodyguard to Todor Zhivkov, our head of state during the Communist years. Apparently he’s a bit dodgy (I won’t elaborate because goats have ears). However, older members of the electorate love him and he looks the sort of fella you’d enjoy having a pint with. Apparently, Angela Merkel had the hots for him.

Election successes of the far-right in France cause us great concern.

11 June, Tuesday

The grade of shade varies about our premises. The weather forecast lady, who always seems severe, underestimated with a chilly 31°C. Our covered terrace achieved 35°C but behind the garden shed it was only 33°C; so that’s where we sheltered with chilled refreshments and embarrassing damp patches. Under the sun it was 15° hotter.

Sadly, it was the last day of the Italian holiday we should have had but didn’t because of the sick dog. We shopped in Kaufland for make-believe duty-free goods and a packet of tramezzino crisps. Not having to pack to go home was the best bit.

12 June, Wednesday

Hailstones the size of golf balls are so passé. Ours were like mandarin oranges, battering the house on all sides. Weather talk is usually boring but this was spectacular. For ten minutes we stood away from our windows, fearing they might break.

Lighter hail, thunder, lightning and heavy rain followed for an hour before a beautiful warm, sunny evening allowed us to gasp at the destruction. Amongst shattered glass and roof tiles every tree, car and building looked like it had suffered a hammer attack.

Our beautiful garden was decimated, like Vietnam after an American Agent Orange party. Neighbours wept!

13 June, Thursday

We won Compost Heap of the Year with countless wheelbarrows of fallen fruit and garden debris. Why don’t decaying figs bear ‘may contain angry wasps’ warnings? I thought as my two rude gesture fingers throbbed with poison. Cracks in tiles suggested our roof isn’t what it’s cracked up to be.

A hundred funerals for little trees and the first ever tears in our garden. No birds sang.

Our cat Osem ate an extremely fresh squirrel and we learned that iconic French singer Françoise Hardy had died in Paris.

Another massive storm sweeping across Bulgaria missed us by 50 kilometres.

hashtagshitday

14 June, Friday

Our dear old cars have a combined age equivalent to that of Ben Hur’s chariot so spare parts aren’t easily found. Mechanic Nikolay confirmed our smithereen-esque mirrors and lights can’t be replaced. Lightning cracked across the sky as both were effectively written off simultaneously. ‘Ullo John gotta getta new motor (and roof)!

We poked at our usually delicious OMV petrol station café banitsas and coffee then honed our moping about skills as rain further soggified our clearing-up task.

The Euro 24 tournament began and by midnight there were 200,000 Scottish football fans in München as pissed off as we were.

15 June, Saturday

In beautiful sunshine and our not quite roadworthy Desislava Daihatsu, we drove up to the food shop in Sheremetya village. All around we saw shattered windows and roofs, walls that appeared to have been machine-gunned and second-hand car dealers’ forecourts containing hundreds of storm-damaged cars.

It seemed strange to accept that our own village had got off relatively lightly. We took time to think about people around the world with homes destroyed by bombs. All things considered, we were amongst the lucky ones.

Feeling slightly less shit, we returned to our personal land clearance scheme, straining emotions more than muscles.

16 June, Sunday

For the first time since Wednesday I saw a golden oriole in the walnut tree. Having feared all feathered friends might have shuffled off their mortal coil, it cheered me like nothing else had done this week. It was a bit of a Noah and the dove with the olive branch situation except there was no flood; June’s sun already has the ground baked hard like a school dinner lady’s pasty.

Am I pruning damaged trees enough? Hoping they’ll bear new leaves this summer, I’m not as brutal as Priyatelkata. Following a heated exchange, I feared she might prune me.

17 June, Monday

At least it was a bright summer morning. Had I got up in the darkness of winter to encounter such widespread skitterings from dogs’ bottoms on the kitchen floor there’d have been a risk of standing in them.

We bought a Lamborghini (or maybe a Fiat… it’s definitely Italian) from the woman who runs the ornamental stonemason’s beside Nikolay’s workshop. If we’ve any problems with the brakes she’ll do us a deal on a nice gravestone.

Celebrating and grieving simultaneously, we had luncheon in the garden restaurant in Arbanasi while waiters brushed up storm damage. Nobody’s hurt but everybody’s stunned.

18 June, Tuesday

We met lovely Maria and Petr at a notary’s office in town to transfer custody of Fyodor the Fiat which we promised to keep clean forever and not just the first month. To earn a living, Petr sculpts three-metre-tall 19th century Bulgarian revolutionary soldiers from stone blocks for public places.

Neighbours Ismail and Amelia can’t earn a living because they’ve no cash to repair their storm-damaged work van. Normally they work like slaves selling fruit and veg in markets. We’re mega-morose but they’re absolutely distraught. Our upfront payment for a thirty year supply of rosovi tomatoes will hopefully help them.

19 June, Wednesday

By 6:00 am we realised we’d been overprotective in keeping la voiture neuve in the bedroom to shield it from Balkan weather.

By 3:00 pm we realised the covered veranda at Gorna Oryahovitsa’s Auto Morgue wasn’t protective enough as a thermometer screamed 41°C. Our cars were weighed and we received 55 stotinki (25p) per kilogram for them. Old motors are cheaper than potatoes.

Back home, grinning gypsy neighbours, eager to work, took delivery of fruit and vegetables to sell in tomorrow’s market. Our new car sat in our parking space no longer littered with battered remains. There were happy tears!

20 June, Thursday

It was already 26°C on our covered terrace when I drank my coffee at 7:00 am. This isn’t uncommon here for August but it’s still only June. Great swathes of a country that almost drowned a week ago are today on fire.

Cat Nouveau is all grown up now. A month ago he decided he was street tough and turned to the outdoor life. But now he suffers the heat in his Tibetan yak hairdo so he’s a house cat once more, snoring long hours under the air-conditioning.

Replacing the cat’s name with mine, you could repeat the previous paragraph.

21 June, Friday

The inaugural day of my 6:00 am kick-off in the garden routine. I beat the heat but not the flies nor the neighbours’ yappy dog. Tidying damaged trees and bushes is becoming less disheartening. New shoots appearing was balm to the brain.

It’s summer solstice time but, although the top hemisphere is now hurtling towards winter and in Homebase in Trowbridge they’ve got Cliff singing Mistletoe and Whine, our weather wasn’t any cooler.

Priyatelkata makes ten mosaic-top tables per day to avoid outdoor catastrophic scenes and temperatures. Not having a flat head is all that saves me from being mosaicked.

22 June, Saturday

It’s Cherry Day in Bulgaria. They call it Chereshova Zadushnitsa (Черешова Задушница, literally ‘cherry stew’). Bulgarians care for the souls of anyone who’s died since Good Friday. Apparently they’re double busy in Heaven from Easter onwards so souls that should get in are hanging around waiting. Wine’s poured on their freshly cleaned graves before they’re decorated with fruit, and we’re knee-deep in cherries this time of year.

I’m only aware of Frank Ifield and the President of Iran dying in that time, but I’ve no idea where they’re buried, and the Iranian lad probably isn’t up for wine on his grave anyway.

23 June, Sunday

My friend Milena explained why our village, but not every village, was battered by hailstones recently.

Every Bulgarian village has a Zmey (Змей), a multi-headed dragon with golden scales. These ferocious creatures ward off the Hala (Хала) which, with a snake’s body and a dog’s head, is the personification of hail and steals from fields, orchards and vineyards. However, if villagers have angered their Zmey, it sulks in its cave allowing the Hala to wreak havoc.

In March a series of kitsch-looking, two-metre-high, multi-coloured plastic letters spelling out I Heart Malki Chiflik appeared in our village square. The Zmey couldn’t miss them.

24 June, Monday

I love my country because every day is celebrated as the day of something or other.

Today’s Enyovden (Еньовден), the day of St Ivan the Herb Gatherer. Before dawn, sorceresses, healers and enchantresses gather herbs for curing childless women, chasing away evil spirits or casting spells for love and hatred. In more state-of-the-art villages we just cut herbs and chai from our gardens for drying.

I hate to bang on about our recent hailstorm but today we felt quite inadequate as our garden has been blown away. So we had nothing to hang up to dry but our freshly laundered knickers.

25 June, Tuesday

Booking a one-way ticket really confuses Easyjet. I know because eight years ago today I flew to Bulgaria from England with absolutely no intention of returning. They still send me emails expressing concern.

I was over two hours at the KAT, de-registering and registering vehicles from our ever-changing fleet. Dimitar helped me. He gave me two litres of the finest homemade rakia to celebrate everything. Double-distilled and matured in oak barrels in his mate’s basement, it’s the stuff that makes Tsars see stars.

Priyatelkata and I didn’t touch a drop but felt happy for the first time in a while.

26 June, Wednesday

The day began gloomily. Our cats often stay out all night but usually return by 7:00 am for full feline breakfasts. At 10:30 there was still no sign of Crado Cat Nouveau until I visited the downstairs loo where he was asleep in the washbasin. He’d been incarcerated at least twelve hours.

Insurance assessor George came to inspect our jigsaw puzzle former roof. A very serious meeting until he sat on the dogs’ squeaky rubber duck on the settee. It squoke perfectly because it was kept inside during the storm. I hope the quacking and laughing doesn’t affect our claim.

27 June, Thursday

Turkey won and progressed in the Euro football thing last night. So if Russia hadn’t come along in 1878, liberating Bulgaria from Ottoman occupation, we’d be celebrating now too. Bloody do-gooders!

Five nice ladies in five chilled offices dealt, or semi-dealt, with insurance affairs too numerous to mention. Having not experienced three parties, fire or theft, we could expect little more from the ladies than them being nice.

Dining at the Asenovtsi with Scottish friends, French Priyatelkata likened the dialect of Glaswegian Brian to that of the Swedish Chef in the Muppets. Luckily, Brian didn’t understand what Priyatelkata was saying.

28 June, Friday

Little more than a fortnight after our general election, the Bulgarian National Assembly has at last chosen a Speaker. So now they can at least try to negotiate the formation of a coalition government. This was never a problem in those heady days of brutal totalitarianism. She’s Raya Nazaryan from Armenia and she’s young and attractive in a don’t-mess-with-me sort of way, but then she’d need to be.

Apparently they’ve an election looming in Britain too. There’s no need to read the manifestos or watch the televised debates. Just remember that Hi Risk Anus is an anagram of Rishi Sunak.

29 June, Saturday

These hot afternoons it’s grand to lie on the settee with jugs of glacial tea and a summer soundtrack. Joni Mitchell, Joseph Canteloube, Bob Marley and Mississippi John Hurt on scratchy vinyl all sooth as Pavlovian mosquitos snarl from their sides of insect screens.

Recovering plants yearn for rain. Thunderstorms will arrive in the coming days. Nervously we’ll look out for mammatusi, clouds from which great ice-laden cellular pouches hang like udders. Not to be confused with Gypsy Mama Tusi who tells fortunes in a tent in a layby on Plovdiv ring road. Does she have cellular pouches I wonder?

30 June, Sunday

In weather so hot my fillings melt when I open my mouth, neighbours Hasan and Slavka have no money, no transport and now no water because of their Communist era plumbing. I bought them twenty litres at the village shop. Embarrassed, they offered me spanners as payment.

I tried to order a book on Amazon. It’s called Rakiya - Stories of Bulgaria, by Ellis Shuman. They said it can’t be dispatched to my delivery location.

We’re Europe’s poorest country, here to provide the so-called ‘developed’ world with cheap labour and jokes. I say ‘we’ and not ‘they’. I love Bulgaria.

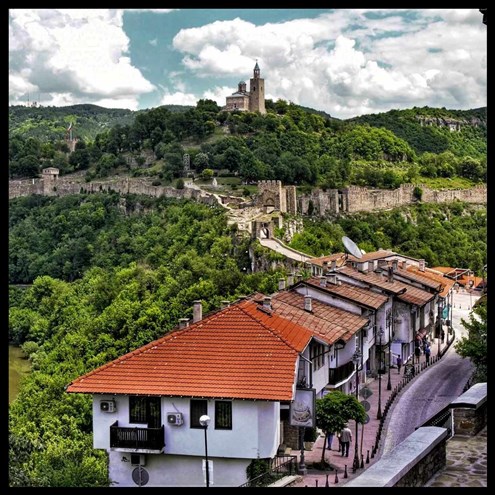

Photograph: Tsarevets (Царевец), our local medieval fortress.