Abto always smiles. He smiles an unforced smile that fills his face in a welcoming way, making it difficult for a person not to instantly feel drawn to him. It’s not the grin of a Cheshire cat. It’s not the bogus beam of an overzealous second-hand car salesman, nor is it the painted smile of the pretty ladies that stand in the laybys on the Sofia road wearing the same short skirts on the hottest and coldest of days. It’s his own, unique smile. It’s not the smile of Madame Lisa del Giocondo but there’s definitely something enigmatic about him.

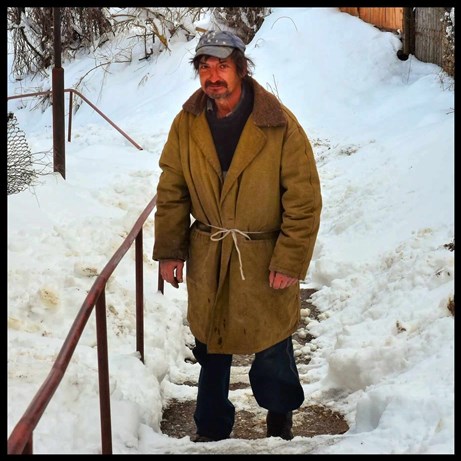

He’s a short man, with a dishevelled appearance that varies with weather conditions and the direction in which the economic wind is blowing. All day long he wanders about our village, Malki Chiflik, stopping to chat with whoever he might bump into. Scanning his surroundings, he examines and probes as if he was the top man at the helm of some sort of organising committee, ensuring that everything runs smoothly. But very little is organised here so he appears to be busier than anyone could ever need to be. He’s busy doing nothing, except smiling. Unlike many of the hardworking and underpaid villagers who grumble constantly about their aches and pains and the government and each other, he gives the impression that he has hardly a care in the world. In terms of material wealth, it’s easy to see that he has virtually nothing but there’s something going on in his head that gives the impression that he is happy with his lot.

Since the days of my youth, a little pastime of mine has been to observe the faces of the people with whom I work, rest and play. From the results of my fifty-odd years of study I have developed a theory that equates people to shrubbery. A major component of this is that the difference between a smiler and a non-smiler can be compared to the difference between a rose bush with a rose growing on it and another without.

The one bearing flowers is significantly more pleasing on the eye than the other, but both can bring pleasure in their own way. The one without the flowers may have bloomed already and is taking a rest, or it might be building up energy to the level required to enable it to bloom in the future, or it might be from a non-floribunda species. Whatever the reason, it can still be a nice feature of the garden. And it’s important to remember that even the sweetest rose may not be what it seems; although flowering it may be struggling with aphids or mildew and consequently, behind its cheery façade, it may not be as happy as first impressions suggest. This same uncertainty might also apply to a smiling face. Who can really tell what the reason is for that smile being there, or not?

From first sight, Abto’s physical features told me that he was from the Romani community. A wide nose, darker skin pigmentation than most Balkan people and thick dark hair remaining thick and dark well into middle age are typical characteristics. So I knew that in his formative years he would have been offered little or no education and that the words he spoke would be a combination of Bulgarian, Turkish and gypsy village slang. No matter what their first language, country people in Bulgaria tend to be only able to talk about keeping livestock or bees, growing fruit and vegetables, or their vast vats of homemade alcohol. The austerity that came with the country’s long periods of imperialist occupation, fascism and communism before being liberated and thrown in at the deep end in terms of the messed up global economics of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries has generated a population where the elderly and a significant proportion of the middle-aged have little or no experience of life outside of rural Bulgaria.

Mixing in a bit of gypsy blood, and the ethnic discrimination that comes with it, renders Abto’s people even more disadvantaged. They are commonly referred to by other Bulgarians as Tsigani (цигани), a word which some of them resent but others recognise as a nickname that, although disparaging, bonds them and identifies them as a proud but badly treated and mistrusted social group in the same sort of way that the ‘N’ word or Paddies might elsewhere in the world. It’s a much stronger word than gypsy which itself, especially when said in a certain tone of voice, can be heard as a term of abuse across the globe. Use of the word Tsigani makes Priyatelkata and I feel uncomfortable so instead we refer to it as the ‘Ts’ word, at which the local people smile to let us know that they understand that we understand its true meaning.

Conversing with Abto turned out to be as difficult as I had expected, but I’ve always loved this sort of a challenge, especially in circumstances that might lead to a long term rapport rather than just five minutes of small talk. It took most of an hour to get through the basics, such as exchanging names. His name is really Abdullah but all Bulgarians have an alternative shortened name, unless their real name is already very short or they are a bit pretentious.

I was telling the truth when I told him that I enjoy the never ending battle to transform my patch of wilderness into a really nice garden, preferring to do all the work myself. So his suggestion that he might become my paid employee wasn’t really feasible. He asked me instead if I could give him a contribution towards the cost of his eye operation. I could see that he had cataracts. They were like small circles of ice; opaque but still allowing through the magical glint that came with that smile of his. In reply to my question as to how much he needed, he answered ‘four leva’ (approximately £1.80) which was strangely and coincidentally the same price as a two-litre bottle of the rough local wine that they sell in our village shop, and nowhere near the two to three thousand leva that is the going rate for ophthalmic surgery.

I didn’t have any loose change. My wallet was stuffed with banknotes of ten and twenty leva denominations. Even with his poor eyesight he would have seen them, so I couldn’t tell him that I didn’t have any money. And I couldn’t tell him that I didn’t have the right money. I couldn’t ask him for change. The chances of a card transaction were beyond unlikely. So I gave him a ten which, as a one off, was very little to me. His foggy eyes lit up and he thanked me with a lingering hand shake, repeating ‘zhee-vot ee zdra-vay’ (живот и здраве), the Bulgarian for ‘life and health’. To my surprise, as we parted, he didn’t set off towards the eye clinic or the bank or his house, but to the village shop. Maybe Nedyalka, the lady who works there, was running a cataract club where the likes of Abto could make small weekly deposits that would be recorded on a membership card to eventually accumulate into a fund capable of taking the sting out of an eye surgeon’s final bill.

People can have cheerful smiling faces for many reasons and, by the end of that first conversation of ours, smiling Gypsy Abto had reminded me that one of those reasons could be that the owner of the smiling face was permanently pissed.

In the years that I have known him he has become a constant source of both amusement and annoyance. The annoying bit is that he started to take my financial assistance for granted, eventually reaching a point where he had come to demand it. During the first eighteen months or so after making his acquaintance, whenever I saw him, which was probably about once a month, I would give him another ten leva (or ten levs, as members of the English speaking community here would erroneously say). This gradually escalated to him loitering near to our front gate once a week, rubbing his apparently empty belly with one hand whilst holding out the other in expectation. His pleas became more and more regular. For a while they were heard twice a week, then it would be once every couple of days until it seemed as though he was there every single day. When we reached the stage where he was shouting over the garden fence I had to have a few stern words with him, and in doing so I enriched my Bulgarian vocabulary in a way that I hadn’t previously imagined necessary. It was then that Priyatelkata renamed him Johnny Ten Levs.

As irritating as this has been, I still can’t help but like him. Even though I only understand about ten percent of what he’s saying, I love his eagerness to pass half an hour of his busy day with a chinwag. Whenever I give him money he always goes overboard to express his gratitude, though I suspect that the long handshakes are merely his way of steadying himself so that he doesn’t fall over in his inebriated state. And that perpetual smile of his, on the face that launched a thousand binges, makes me want to be his friend in this place where he is barely tolerated and largely despised because of his ethnic background and his insatiable thirst.

I thought about giving him food instead of money but Bulgarian friends and neighbours tell me that he’d probably sell it or exchange it for alcohol. In an attempt to disguise the fact that he’s a bit of a scrounger, when we’re discussing the possibility of money being handed over he almost always offers to do some work in our garden. I probably could find him something to do but his work ethic is questionable so I just give him the cash without expecting anything in return. It’s probably easier that way, for both of us.

Sometimes I put myself in his down-at-heel galoshes. He’s a poor native with nothing. I’m an immigrant with a big house, a lovely garden, a relatively nice car and enough money in my pocket to enable me to not have to think about going out to work. So I can understand why he comes to me for help. He recognises the disparity between us but never shows any sign of resentment. Bulgarians never do. They don’t see Western Europeans as people who are stealing their jobs or their land, but they do see Western European countries as a places that are stealing their doctors, nurses and engineers.

Once, as I was walking down the lane to go to the shop (for yoghurt and eggs, not for rough local wine) I saw Johnny helping some Bulgarian neighbours with their overgrown trees. As they were doing the lopping, he was dragging the branches down an embankment and cutting them up into smaller pieces to burn. I thought to myself how kind these people were to give him some work from which he’d earn a little money and some self-respect. On my homeward journey twenty minutes later, I saw him sitting on the grassy bank with a plastic beer bottle in his hand, seemingly oblivious to his would-be employers who were shouting and screaming at him from the other side of their garden fence. I suspected that his performance had fallen short of their expectations and I thought to myself how kind I was to have never put him in a situation where it was likely that I’d end up screaming and shouting at him.

Luckily his presence is usually preceded by an alert from his early warning system. Although I have been unable to find out exactly who, there seems to be someone round about who looks after him. Someone has rescued him from the street like we do with cats and dogs. About once a month he is miraculously clean shaven and re-clothed, especially in summer when he is often seen wearing Hawaiian shirts that glaringly stand out against the usual attire of Bulgarian village people. At some point in his life he must have worked as a labourer because occasionally I see him wearing a high visibility vest with the name of a road building company printed on the back. When he’s clad in these brightly coloured garments acquired during the construction work and / or tropical phases of his life, I am able to see him approaching quite some time before he can see me and therefore I am able to take evasive action. The meandering nature of his wine-fuelled gait further reduces the effort required to avoid him. Using every centimetre of the width of the lane that leads past our house, it takes him an eternity to arrive from the point where he is when I first spot him. In this respect his fitness regime must be admired as he seems to be able to do his recommended 20,000 daily steps in the space of 500 metres.

I’m tempted to say that his winter apparel is much different to his summer wear, though I suspect it may consist of exactly the same clothes but hidden under his genuine acrylic heavy sheepskin coat, at least one pair of past-their-sporting-best track suit bottoms and galoshes that may or may not conceal shoes and socks. He makes allowances for fluctuations in air temperature by adjusting the knot on the piece of string that holds his outfit together.

In the Malki Chiflik village square there stands a huge, communist era, rusty iron bus shelter that’s big enough to be considered an acceptable alternative to our community centre. Recently it has been decorated with a magnificent piece of street art, thanks to the skills of our local equivalent of Banksy. This brightly coloured masterpiece depicts a handsome young soldier fitted out in the hat and uniform of the brave body of men who fought against the Turks in the late nineteenth century to liberate our country from the cruel oppression of the Ottoman Empire. I can see that the handsome young soldier in the painting has all the facial features of dear Abto, including the smile. I’m not sure if this is a mere coincidence or if the artist has some sort of respect for our man. Maybe he or she was just taking the Mikhail, but there is definitely a clear resemblance. I mentioned this to other people that I know in the village who, after their laughter had subsided, pointed out that it couldn’t possibly be him because the man in the picture didn’t have a wine bottle in his coat pocket. To put the matter straight I considered taking Abto along to the bus shelter with me, but it would cost me at least ten levs, it would take all day and he probably wouldn’t be able to see it anyway. So it remains a mystery.

I’ve told him my name at least a dozen times but it doesn’t seem to register. I never hear my name from Priyatelkata either, well at least not my real name. She always calls me ‘My Love’, often shouting it at the top of her voice when trying to attract my attention from the other end of our big garden. Johnny seems to have picked up on this, probably because she makes more noise than I do, so he too sometimes shouts ‘My Love’ when he wants to talk to me. It’s nice that he enjoys our conversations but I worry a little that our neighbours, on hearing him calling me by the same pet name that Priyatelkata uses, might think that he and I are in a gay relationship. His little cap and his moustache, not dissimilar to Freddie Mercury’s, do make me wonder a bit.

In recent months his nickname, Johnny Ten Levs, has been shortened to just J.Lev, even though he’s still Johnny from the block. Some readers might not understand what I mean by this but I know that at least the glamourous American singer, actress and dancer, Jennifer Lopez will. She’s an avid fan.

I often wonder if Johnny really is still on the block or even the planet, especially in winter when sometimes I don’t see him for weeks on end. I’ve been told that he drinks anti-freeze to combat the climatic extremes of the icy months. I worry that when I’ve refused him his ten levs he has starved to death in the bitter cold, and I worry that when I have given him ten levs he has spent it unwisely and died of alcoholic poisoning.

I know he lives in a house somewhere in our village and someone is looking after him. I’m tempted to follow him home one day to learn more about him but I would run the risk of bumping into the entire Ten Levs family. He gets by and he smiles. Wherever he lays his hat, that’s his barstool. Maybe his life isn’t so bad, but I’m thankful I’m not him.

Photograph: Our very own Johnny Ten Levs.