If we were allowed to make up our own birth signs I reckon I’d probably go for Hermes (not herpes) because in Greek mythology, he was the god of travel and a lot of Greek mythology is set in Bulgaria where I live and I feel it’s nice to patronise the locals.

I’ve never been any good at staying in the same place for very long. You could say I’ve been around a bit in my time. I’m always itching to see what’s round the next corner, no matter where I am, even if I’ve only recently arrived from round the previous corner. Wherever I lay my woolly Leeds United scarf, that’s my home! To be set on with the task of being god of travel I expect you’d have to have the same problem (though I no longer see it as a problem now that I’ve been round so many corners). I wonder if this was something encountered by Hermes (not Hermesetas) during his time as a divine being.

As a consequence of not being able to sit still I’ve travelled on a lot of aeroplanes where you do have to sit still but it turns out to be worth it in the end. I’ve emptied my pockets, taken my boots and belt off and placed all my fluids in clear plastic bags hundreds of times. I’ve manoeuvred red hot chicken and vegetables from countless little foil dishes to my mouth or the front of my trousers using cutlery made from a material not as tough as the chicken itself and with my elbows simultaneously trapped just above my hips as if in a sort of a straitjacket situation but probably not as comfortable. Although the main meat (or meat substitute) bit of an in-flight meal only weighs round about sixty or seventy grams, I’ve calculated that down the years I have consumed enough of this stuff to reconstruct a whole flock of chickens, most of a heifer or a mushroom cloud. The various slices of vacuum packed cake that have passed through my digestive system at forty thousand feet would cumulatively amount to something akin to Kim Kardashian’s wedding cake, I’ve consumed enough strawberry fool to float the General Belgrano and, to my horror, disposed of enough single-use plastic to construct a full scale model of a Boeing 747.

My carbon footprint must be at least a size twelve but, in my defence, I would put forward the notion that for a lot of the years in which I was flying around the world people just weren’t aware that they had carbon feet. It’s a relatively recent thing and the past can’t be changed. I worry about greenhouse gas emissions to the extent that I’ve never given in to Priyatelkata’s pestering for us to have a greenhouse in our garden but, as I see it, a plane that I’m sitting on for any given journey would still be going to wherever it’s going to, even if I wasn’t on it. But introducing an extra greenhouse to the world is a different kettle of carbon dioxide and I’m really not fond of courgettes anyway. I don’t travel by plane every week as people like Kim Kardashian, Richard Branson, Rishi Sunak or Biggles with his White Fokker do and when I’m at home, which is the vast majority of the time now that I am in my twilight years, I don’t drive my car very much.

Anyway, the thing is, I’ve been on loads and loads of aeroplanes but, having been a Roman Catholic for the first few years of my life, I continue to live every day wracked with a need to offload my feelings of guilt. How many Hail Mary’s would Father Crawley have had me saying if he knew that I’d recently been with the Ryanair polluting people from Sofia to Vienna and back in the space of a fortnight. What’s the nitrous oxide to Hail Mary’s ratio? There must be a chart on a website somewhere.

Ryanair, being an Irish airline, must have a few Roman Catholics on board themselves, so the fact that their aircraft appear to be constructed from recycled parts from old Messerschmitt ME109s instead of brand new machines suggests that they might be trying to be a little more environmentally friendly. That feeling of remorse about the melting icecaps must really niggle in their undercarriages. As I’m welcomed aboard with an announcement from Ryanair’s Captain Fantastic in the cockpit informing me that he hopes I’ll enjoy the next three hours confined to a space only five millimetres bigger than the dimensions of my body in every direction, which is a much greater penance than anything that Father Crawley ever handed out as I left the confessional, I smile in appreciation of the fact that the more people they ram into an aircraft, the fewer flights there needs to be.

Anyway, the next thing is, out of all these flights that I’ve been booked up on, I’ve only ever missed one of them. I can imagine that going away on your holidays and missing your flight might bring on a cluster of negative emotions. But whenever I’ve been travelling to meet the needs of, and at the expense of, my employer, experience has told me that if I wasn’t in my allocated seat as the wheels left the ground I’d not only a be a bit hacked off about it but also prone to being verbally abused by the employer’s earthly representative. I can confirm that there’s absolutely no fun in sitting in an airport departure lounge with a redundant boarding pass and thinking about the red hot chicken and vegetables in a little foil dish that I should have been tucking into as I prepare myself for receiving a torrent of expletives from an irate personnel officer at the other end of a phone line.

I was nineteen years old at the time of me missing a plane this one and only time. I’m more than three times that age now and, although there have been three or four minor scrapes with tardiness there has never been a repetition. The minor scrapes, I would add, were always due to circumstances that were never ever my fault apart from, that is, the occasion on which I set the bedside alarm clock for the wrong time, and when I took the wrong turning off the road to the airport, or when I dithered about a bit too long over what kind of massive Toblerone bar to buy in the duty free shop or when customs officials caught me trying to smuggle more than the normal allowance of massive Toblerone bars by concealing them in an intimate place.

As a nervous teenager I was working as a Navigating Officer Cadet for a company called Scottish Ship Management. They won’t mind me mentioning their name because, as a consequence of shifts in global economics, they no longer exist. Hard times in the world of merchant shipping and the caution required in financial terms to keep their fleet of rusty tramp ships afloat meant that corners were cut so the rust grew rustier, the cargoes became scarcer and the destinations became more obscure and/or dangerous. Employees of other shipping companies tagged us with the epithet ‘Glasgow Greeks’. I hope that the good people of both Glasgow and the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula will forgive me for repeating this bit of political incorrectness but anyone who has any experience of Glaswegian seafarers or Greek cargo ships will know exactly what they meant. In actual fact we seagoing employees of the company became quite proud of the nickname in a peculiar sort of way, especially when we heard it mentioned by port authority workers, bar girls and police officers in places as far apart as Jakarta, Port Said, Quebec and Greenock.

I was flying out to begin the third trip of my illustrious career as a salty sea dog so, although still an apprentice, I was feeling fairly confident about the things that I was likely to encounter in the coming days, weeks and months.

‘You’ll be joining your next ship in Newcastle,’ I heard the personnel officer say down the phone, ‘So you’ll need to get yourself off to the Consulate in Manchester to get a visa stamped in your passport before you go, otherwise they won’t let you in.’ His name was Jimmy, by the way. It had to be. He was in Glasgow. Apart from him, another Jimmy was the only other person in the shipping office that I ever had to speak to. He dealt with expenses claims. Sometimes people would just call him Jim to distinguish him from the first Jimmy, thus avoiding confusion. The rest of Glasgow looked on in dismay.

I struggled to get my head round the need for these documentary requirements as I was living in Leeds at the time and Newcastle wasn’t much further away from home than Manchester was. I was aware that they spoke a completely different language up there and had a few strange customs but I was surprised that I’d need to be vetted in any sort of way before crossing the River Tyne.

My grandmother was from Sunderland. For the first time in my life this had become a cause for concern. How angry would Jimmy have been if my visa application had been turned down on the grounds of a blood relative being a supporter of Newcastle’s arch rival football team? And why Manchester? As a resident of Leeds I could think of no place on earth worse than there to send me to. I’m not in any way racist but Wilson’s Great Northern Bitter, which was popular on the dark side of the Pennines in the 1970s, was something that I found quite difficult to swallow along with the way the people who lived there called a bread roll a barm cake and that being there was like being in a tropical rain forest but without the tropical bits and the forest bits.

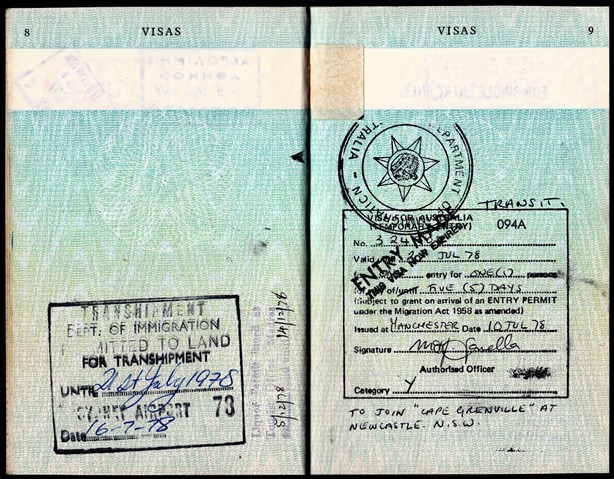

My visa issued at the Australian Consulate in Manchester on 16th July 1978.

In response to my protestations, Jimmy consoled me with the words ‘New South Wales’. They were sending me to Australia, which made much more sense. I hadn’t known that there was another Newcastle in the world but from having a pint and a chat with a bloke called Denis in my local pub who had also worked on ships many years earlier and whose great grandfather had been a marsupial, I learnt that the Newcastle that I was to be heading for was famous for its coal production. I lost contact with Denis not long after he had one trip to the pub too many and he lost contact with reality but I have other sources of information nowadays from which I have just today read that Aussie Newcastle still has the largest coal exporting harbour in the world. So when we use the idiom ‘carrying coals to Newcastle’ we should really check up on which Newcastle we’re talking about; the Geordie one or the Bruce and Sheila one.

At this point I’ve stopped writing for a while to consider how big Australian Newcastle’s carbon footprint must be. They’re going to need to recycle an awful lot of empty beer cans to compensate for it.

The following day I travelled by train to Manchester to get my Australian visa. The day after that I travelled to by train to Glasgow (which ironically stopped at English Newcastle en route) to claim back from Jim (not Jimmy) the expenses I incurred on my trip to Manchester to get my Australian visa. He also gave me my tickets for the flight to antipodean Newcastle. Looking through them to make sure I was happy with the details I saw that there were three flights; one from Leeds to London’s Heathrow airport, one from Heathrow to Sydney’s big international airport and another from Sydney’s little bushwhacker airport to Newcastle.

However, and I told Jim this in no uncertain terms, I wasn’t happy with the details. My flight from Leeds was going to land at Heathrow’s Terminal One less than an hour before the flight to Sydney would be taking off from Heathrow’s Terminal Three. First of all, I had to get him to explain to me the concept of airports having more than one terminal building; this only a day after my mind had been blown away by the discovery that Manchester had two city centre railway stations. Secondly I needed him to explain to me how I would get off one plane, negotiate my way to another building and get onto another plane within the space of fifty-five minutes. He told me that I would run. Finally, I asked him what I should do if I missed the plane to Sydney. He told me that I wouldn’t. On the return train to Leeds I sat and worried and wished I’d spoken to Jimmy, who was Jim’s senior, about the big challenge that lay ahead of me.

The next day I was free to lay in bed until late for the last time in a long time, pack into my bag everything that meant anything to me (mainly a couple of dozen Rolling Stones cassette tapes as my source of entertainment as I crossed vast oceans and my Leeds United scarf in case it got cold in the Tropics) and go for a pint with Denis who told me that if I missed my plane at Heathrow I should just go for a pint until the next plane was due.

The day after that was the day on which the action really started. I didn’t trust the Leeds buses to get me, the Rolling Stones and Leeds United to the airport on time so, with the begrudged consent of Jim, I went by taxi. The driver dropped me off precisely at the time I had planned to be outside Terminal One at Leeds/Bradford International Airport. I was confident that it was Terminal One because, forty-five years later, Terminals Two, Three, Four, etc. still haven’t been thought about, let alone been built. Smiling but feeling a little apprehensive I dragged the cassettes and football scarf inside the building, checked the departures board and then evacuated my bowels on the spot into my lucky travel underpants when I saw the words ‘delayed one hour’ written in bright lights next to the details of my flight.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have my mobile phone with me because at that stage of the rampant global advance in technology they had yet to be invented, so I found a public phone box and called Jimmy. I was told that he’d just gone out to lunch in a Glasgow pub with some very important people he was entertaining and would be back in about an hour or so or tomorrow but a note would be left on his desk to phone me back as soon as he could. There was little point in me hanging around in a telephone kiosk waiting for him so I decided it was time to put on a brave face and take on the world; well at least some of the world, and probably not Australia.

I went through all the airport procedures you had to go through in the late 1970s which didn’t include being scanned or patted down or felt up or sniffed, as they do now, but did include donning a leather aviator hat and goggles and listening out for the public announcement ‘chocks away’ rather than today’s ‘you’d better look sharp and finish your pint because your flight is boarding at gate number so-and-so’. The plane to London lifted off from the Leeds runway exactly one hour late, exactly as the departure board had promised. At Heathrow I would have exactly negative five minutes to get on the plane to Sydney. The British Midland Airways young lady flight attendant tried to cheer me up with a free coffee in a pot mug and a couple of custard creams but she didn’t have a great deal of success. In fact, all of the passengers looked a bit glum but that wasn’t surprising because they were flying away from Yorkshire to go to London.

People at the Qantas airlines desk at Heathrow’s Terminal Three confirmed that the flight to Sydney had departed on time and I had missed it but, thanks to the efficient working practices of the baggage handlers, my cassette tapes and my football scarf hadn’t. I explained my predicament and they told me that I should speak to whoever had booked and paid for the flight and that they were sure something would be sorted out.

Their best piece of advice was, ‘Go and have a cuppa tea love, and unwind a bit.’

I phoned Jimmy, hoping he had returned from the pub. Back in those days the pubs in Britain closed for a couple of hours in the afternoons so I was reasonably sure that he would be at his desk by 3:30. Unless, of course, he had gone to the Red Parrot which was in Buchanan Street (the same street as our shipping office) and which was taking part in a Glasgow City Council experiment to see if all day pub opening would be a success. Who could have ever imagined that a pub being open all day in the middle of Glasgow might not be a success? Anyway, he had been out with a couple of the company’s senior engineering officers so they had gone somewhere a bit posher than the Red Parrot and their session had ceased at a civilised time.

During our conversation we both conducted ourselves in a calmer and politer way than we had expected of each other. Having made it clear that I was a bit unhappy there followed a couple of minutes of silence as Jimmy thought about the situation and I pumped ten pence pieces into the payphone which seemed quite wasteful, especially when considering the financial difficulties that we had been told that the shipping company was in. He said a couple of words that would have cost him at least five Hail Marys had he been in Father Crawley’s confession box and then told me to go to a newsagent to buy a British Telecom phone card and call him back in an hour. For anyone less than a hundred years old perhaps I should explain that the phone card was a sort of prepaid debit arrangement that fitted into a slot in some public telephones and was slightly cheaper, more convenient and much less uncomfortable than having a pocket full of coins to feed the hungry machine with. Buying such an item from a shop meant that I would get a receipt and I’d be able to claim back on my business expenses the significant amount of money that I presumed I’d be paying for phone calls while my predicament was being sorted out from afar.

I rang back an hour later to be told, ‘Ring back in an hour!’

Another hour later I heard the same. It was repeated a fair few times with the level of my despair increasing in inverse proportion to the number of units remaining on the phone card. I could see through a window in the distance that although we were in the middle of summer it was starting to get dark outside. Jimmy would want to go home soon. I wanted to go home soon. I rang him again.

‘Phone me back first thing in the morning.’ he said. ‘I think I’ll have some good news for you then.’ The best news that I could think of at the time was that I’d be going back to Leeds and getting a job in a bank.

‘What am I going to do tonight?’ I asked in a voice in which it took no effort to maximise the pathos of.

‘Buy some sandwiches and a couple of cans of beer, stretch yourself out across some seats and try to get a bit of sleep. You’ll need to be fresh and alert for tomorrow.’ There was another Father Crawley moment, contributed by me this time, and then the phone line went dead.

Feeling utterly dejected I did almost exactly what he said. I got four cans of warm McEwan’s Export instead of two. Buying a four pack, the promotion board in the shop stated, would save me five pence so I did this as a good turn, bearing in mind that Scottish Ship Management was ankle deep in a financial mire.

I couldn’t sleep. The aircraft departures and arrivals had stopped for the night. The airport staff, apart from a few cleaners, had all gone home. The passengers and their friends and families who were waving them off had all gone off or gone home. Other people appeared who seemed to take pleasure from mysteriously wandering around airport terminal buildings all night. They were the sort of people who I had encountered before, mysteriously wandering around bus or railway stations all night, but a bit posher. To take my mind off the awful things that I thought might happen to me during the night I started to think about the awful things that might happen to me the following day. My big concern was that any rearranged flight that Jimmy & Co managed to book for me might get me to Newcastle in New South Wales after my ship, the m/v Cape Grenville, had sailed. What in the name of Evonne Goolagong would I do if that happened? I knew that once loaded up in Newcastle the ship would be heading for the Philippines. I wanted to ask the people at the Qantas airlines desk if there was a bus replacement service from Newcastle to Manila.

It was at this point that I realised that if you take the word ‘Heathrow’, change the first letter and add a space just past the middle, it gives you ‘Death Row’. So I woke up the man who worked at the all-night shop to buy a book by Spike Milligan and spent the whole night reading it. At round about half past three in the morning I laughed out loud at something he had written. Only he could ever get a laugh out of me in such dire circumstances. For that I will be eternally grateful to my dear Mr Milligan.

‘Ring back in an hour!’ a weary sounding Jimmy said when I called him at eight o’clock in the morning. It wasn’t the best news but it cheered me up because I hadn’t expected him to answer the phone at all at that time of the day. Jimmy was on the job!

‘Great news!’ said Jimmy when I phoned him on the stroke of nine o’clock. ‘I’ve got you a seat on a flight that goes direct to Sydney, taking off just before eleven.’

‘Oh brilliant!’ I exclaimed, ‘That’s only a couple of hours.’

‘Actually it’s fourteen hours’ he said, pulling the wombat’s wool rug from under me.

‘Will I miss the ship Jimmy?’

‘No,’ he said ‘It hasn’t arrived there yet. The flight time to Sydney is twenty-six hours, we’ve arranged for a shipping agent to pick you up at the airport and transfer you to where the local flight leaves from and there you’ll only have three or four hours to wait for the plane to take you up to Newcastle. That should only take an hour or so, as long as it’s not too windy. So you probably won’t miss the ship.’

Probably is such a strong word, I thought to myself as I wandered over to the shop for a pile of sandwiches because I was starving and miserable, four more cans of beer because I was thirsty and miserable and another Spike Milligan book because I was bored and miserable. Collecting a new set of travel documents from the people at the Qantas airlines desk cheered me up more than any of these other things.

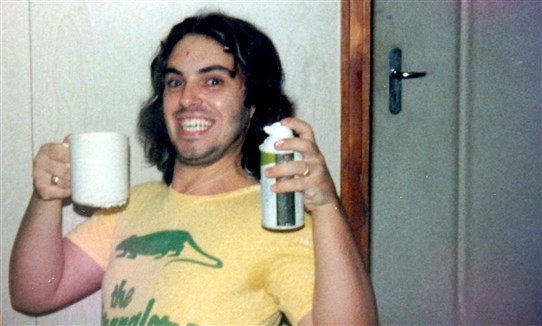

Me in the gents’ toilet at Heathrow airport trying to convert a warm can of McEwan’s Export into a decent pint.

I slept for a couple of hours. I talked to a man who was really upset because his flight was delayed by twenty minutes and things hadn’t been going too well with his wife just lately and she had agreed to pick him up at the airport in Cairo but if he was late she probably wouldn’t hang around because he was sure she was having if off with the gardener who only worked there in the afternoons and he’d have to pay for a taxi while she was at it with him at home in the shed. My heart bled for him (the man, not the gardener) for a couple of minutes. I went to the toilet six times, I walked full circuits of the inside of the terminal nine times, I checked the departures board eighty-seven times, I phoned my mother to tell her about the calamitous situation I was in and she asked what sort of meat had been in the sandwiches that I had bought. Don’t tell Jimmy or Jim but I used the phone card to pay for the call. Late in the afternoon I bought a copy of the London Evening Standard to see if there were any vacancies for banking staff in the jobs section. There weren’t but Heathrow Airport was looking for night time cleaning staff.

I had a window seat on the plane. I love a window seat but they could have put me in the overhead baggage compartment on this particular occasion and I would have been just as happy. In the thirty-six hours since I had left home I had travelled three hundred kilometres and only had another seventeen thousand to go. A daunting prospect but I was delighted to be on my way at last. I suspected that Jimmy and Jim were equally happy with the developments late that evening as they would be able to have at least one day off from listening to me on the phone banging on about being a displaced person having to sleep rough in the departure lounge of one of the world’s biggest airports.

What was I going to do to amuse myself for the twenty-six hours that I was to spend confined to my seat? It seemed strange that out of the window I would see the enormous expanses of the Indian Ocean and the Asian continental landmass and of space itself, but on my side of the window, where I was quite happy to remain despite the mild feelings of claustrophobia, I had barely enough space to eat the peanuts that were forced on me at regular intervals by a caring cabin crew doing their utmost to relieve the passengers’ boredom.

I spent the first hour thinking about what I could do to keep my mind active for the other twenty-five hours. My first thought was that I would deactivate my mind and catch up on some much needed sleep. Also I had half of a Spike Milligan book to read (the latter half) and I had paid a pound for a set of Qantas airlines headphones that looked remarkably like a stethoscope which I plugged into a hole in the armrest of my seat to enable me to listen to the in-flight entertainment. Adjacent to the hole there were two dials, each with the numbers one to ten embossed upon them. One dial was for controlling the volume and the other was for selecting a channel. Channels that each played exactly one-hour long audio recordings on a constant loop for the time it would take us to fly from Haringey to Botany Bay. These recordings were audio only, of course, as video entertainment back then was still only present in the mind of George Orwell.

The channels contained some unusual stuff and the sort of thing you could only find on a long haul airline flight. Examples of the available material included funny moments with great comedians that you’ve never heard of before (or since), interviews with famous jockeys (horse racing jockeys, that is, not items of underwear), the best of Abba (so far… remembering that we were still only in 1978 so the world had yet to be subjected to Voulez-Vous and Chiquitita) and the music of Australian jazz legends such as Blind Willy Billabong and Charlene Sheepdip. Channel five was the sound to accompany a film that we were promised would be shown later in the flight but at that point was just silence. The best of television’s Coronation Street from 1967 to 1969, the greatest performances of mime artist Marcel Marceau, highlights of the 1974 World Snooker Championship and a channel entitled ‘Especially for the Kids’ comprising of sixty minutes of Katie Boyle shouting ‘now just shut up and sit still’, were other titbits of entertainment made available to us by means of state of the art technology. I hadn’t had so much fun since the new zebra crossing was opened outside the shopping centre in the fashionable Seacroft district of Leeds.

From the cockpit, Captain Australia (the world’s first marsupial superhero) announced that we would be landing in Naples, Muscat, Bombay, Singapore and possibly Perth for refuelling purposes only. Why only possibly Perth? Was there a chance that we wouldn’t make it that far? I would have liked to have got off the plane for half an hour at each of these to send postcards to Jimmy. Many years later, as a daily commuter on my way to work, I was reminded every morning of the pilot’s words as the computer generated station master at Chippenham advised passengers that the train would be calling at Bath Spa, Oldfield Park, Keynsham and Bristol Templemeads. Great Western Trains didn’t give us complimentary snacks as we pulled away from platforms but then, on the other hand, I never had to endure a wait of thirty-plus hours, despite the seemingly perpetual problem of signal failure on the Corsham side of Box Tunnel. The round-the-world stops that Qantas provided came with much better things to see from the window than the Monday to Friday 7:50 give-or-take-half-an-hour service that trundled across bits of Wiltshire and Somerset ever did, and comparing the five different arrangements of palm trees, fuel tankers, cigarette wielding ground staff, dense clouds of black smoke and fire engines helped to pass some of the time on this journey to New South Wales.

In the late 1970s, airline seating configuration was such that no matter where you were sitting there was sufficient room for you to get up and walk around without disturbing other passengers, even those sitting right beside you. So a little time could be passed stretching the legs on the way to the generously sized toilet cubicle (complete with shower and Jacuzzi but sadly no bidet) or to a window to look at the generously sized ocean below or to go and chat with the people in the area designated for smokers which was much more generously sized than the no smoking seating area. Without any physical partitions, there always seemed to be cigarette smoke everywhere in an airline cabin so I could never understand why they went to the trouble of even attempting to impose such segregation. But the inconvenience of the inevitable suffering from respiratory diseases was probably outweighed by the luxury of being able to walk about up and down the aisles, which I’m sure must have improved passengers’ blood circulation and would have averted the threat of deep vein thrombosis had it existed back then.

What I hadn’t anticipated was spending twenty of the twenty-six hours talking to the well spoken English lady from a leafy suburb of Surrey who was on her way out to visit her daughter who lived in a leafy suburb of Sydney and was looking forward to seeing her new granddaughter for the very first time. She was a very interesting woman who told me many things about Australia including the best way to get to and from it by plane. As a frequent visitor she said that she preferred to take the flight that only took twenty hours to get there from London but usually she went for the twenty-six-hour service because it was ‘loads, loads cheaper!’

Eventually the lights went down and the in-flight projectionist began to project the in-flight film onto three big white canvas screens unfurled mechanically and as if by magic from the ceiling, each a third of the length of the cabin apart. So although listening to it wasn’t compulsory, watching it was. Like Big Brother in reverse, there was nowhere you could go where you couldn’t see it. To make things worse, it was the newly released classic, Smokey and the Bandit that later won Academy Awards for the picture with the best use of citizens’ band radio jargon, the best police car chases in which at least a dozen cars with a dozen chickens on their back seats are overturned and/or driven off bridges into shallow rivers and the best people going ‘Hmmmphhh!’ Burt Reynolds’ basset hound called Fred (playing himself) was nominated for the best leading actor award but Burt Reynolds wasn’t.

By then I was sick to the back teeth of Ena Sharples, Lester Piggott and Abba from the entertainment package; if the truth is to be known, I had already become sick of them many years before I boarded the plane. So I unplugged my headphones and the Surrey lady did the same and we chatted for a while about ships and travelling and the Rolling Stones and better films than the one on the screen in front of us until other passengers who were enjoying the film on the screen in front of us told us to ‘Shush!’

I closed my eyes and silently cursed Jimmy and Jim over and over again. It must have been like a sort of frustrated shipping company employee’s counting sheep exercise as eventually I fell asleep. When I woke up an hour or two later I found that my new friend was asleep with her hand resting on my arm and her head tucked into my shoulder. Was this an accident or did she have some sort of intentions? Oooooh!!! Guessing that she was in her early forties I had told her earlier that she didn’t look old enough to have grandchildren. She smiled and I thought nothing more about it, but maybe I had made a mistake. I was a young merchant seaman less than half her age, trying to build up the bad reputation that was one of the requirements of my chosen profession. I couldn’t possibly become emotionally involved with a young middle-aged, well spoken, well educated, amusing and attractive woman with enough money in her pocket to travel to Australia two or three times a year. Eighteen months later on a rainy Monday morning I found my personal circumstances had changed somewhat as I sat on a number nine bus on Leeds Ring Road wishing that I’d offered her my red hot chicken and vegetables in a little foil dish and asked her for her phone number. But I hadn’t done, and she’ll be in her late eighties now if she’s still about.

I was glad when the plane landed in Sydney. I said goodbye to Miss Surrey and with a big smile she told me that she’d probably see me again on another flight out from London. I tried to appear sad about our parting but my arse and I were so glad to be not sitting down anymore after more than a day of sedentary suffering that I probably wasn’t very convincing.

I was pleased to see my Rolling Stones cassettes and Leeds United scarf again, although they were encased in my suitcase along with the clean clothes that I was absolutely desperate to see. If suitcases could express human emotions I’m sure I would have got a barrage of ‘and where the hell have you been for the last two days?’

The shipping agent met me, as expected. He told me that because there were a few hours to wait for my connecting flight to Newcastle from the other Sydney airport, and because there wasn’t much to do at the other Sydney airport, it would be a good idea to have a beer in the bar at this Sydney airport. As a consequence of the lengthy delays and the crossing of countless time zones, my brain was having great difficulty establishing what time of day it was and after a bit of conferring with my liver and kidneys, it settled on the likelihood that it was early morning. If only my vital organs had collectively been able to adjust my wristwatch I might have returned to the real world a bit sooner. I wasn’t really in the mood for alcohol so I asked for a coffee.

The woman behind the counter at the bar/works canteen sort of place said, ‘The coffee ran out a few days ago but we’ve got beer.’

‘Can I have a glass of milk?’ I asked, giving away the secret that I wasn’t the slightest bit antipodean.

‘Sure! What flavour?’ She seemed only slightly shocked.

Nervously I enquired, ‘What have you got?’

She offered me a wide choice. ‘Strawberry, banana and… err… chocolate. Though I think we might be out of chocolate.’

‘I’ll just have ordinary unflavoured milk please’ I said, bewildered by the range available.

‘Ah, you mean cow’s! We don’t sell that’. This time she sounded a bit more shocked.

I ended up with a can of an ice cold, fizzy, locally manufactured, Coca Cola type beverage, suggesting to my shipping agent friend that it should be called Coca Koala but he didn’t see the joke because he didn’t know what it was because he only ever drank beer.

‘Only Sheilas drink Coke,’ he said, ‘… in their gin!’

Feeling suitably refreshed (well he seemed to be refreshed even if I wasn’t) he helped me and my belongings to his car and dropped me off at Sydney’s domestic airport with almost two hours to spare before my flight was due to leave. Taking in its terminal building that had the appearance of a modern semi-detached suburban house and its runway that looked like a modern semi-detached suburban street, I felt that I had stepped into a more relaxed world.

There was no sign of a departures board but there was a woman wearing an AeroPelican Airlines baseball hat who was able to tell me ‘Your plane’s delayed two hours because of the bad weather. You can have a beer while you’re waiting.’

A bit startled at suddenly finding myself back in airport hanging about mode, I hesitated to speak and a cold can of Toohey’s lager was thrust into my hand. It was so cold that it stuck to my skin so even if I had decided to decline the woman’s offer I would have had to wait an hour for it to defrost before I could give it back to her.

As we sat together on the bench outside the terminal building in the warm sunshine, I said to her, ‘What bad weather?’

She answered, ‘It was icy this morning so it wasn’t safe to fly until the sun had been on the plane for an hour or two. It’s the first frost we’ve had in Sydney since 1942. Because of this the early morning flight only left here forty minutes ago. If you’d got here an hour sooner you’d have been on it’.

I apologised for my earlier absence, pointing out that it was due to the fact that I had been drinking carbonated kangaroo body fluids with the shipping agent in the bar at the international airport.

‘Shame.’ she said, ‘You would have been in Newcastle by now, having a beer!’

Having boarded the final aircraft of my arduous journey I was able to calculate accurately that only twenty percent of the seats were occupied. Two ladies, with more luggage than Scottish explorer John (not Jimmy) McDouall Stuart had with him on his 1862 expedition to find Alice Springs, and I occupied three of the seats, leaving the other twelve empty. It was the smallest plane I had ever travelled in. Without moving I could see clearly out of the windows on both sides but struggled to avoid the blow-by-blow account of the two ladies’ shopping expedition in the big city.

The pilot shouted through the curtain from the cockpit to let me know that if I could wait until we were in the air his mate Gazza would get me a beer. I politely said no to this and as the plane took off I noticed that Gazza was not on board. Gazza must have been employed by AeroPelican Airlines for the sole purpose of handing out cans of beer to passengers and, because of my responsible attitude to drinking alcohol, he had a day off. During the short flight the plane didn’t seem to rise very far above the ground so the pilot was able to shout me the names of the hills and creeks in the beautiful, mostly forested national park below, adding a few amusing snippets of local history; tales based mostly on hungry crocodiles, thirsty Sheilas and more Toohey’s lager than you could fit into a rowing boat; the story told around the latter being something that he knew for fact to be true because he and Gazza had once tried it.

Kev, the second shipping agent of the day shook me by the hand on the runway at Newcastle airport, which wasn’t quite as flashy as the airport at which I had boarded the plane in Sydney. I thanked the pilot, wondering if I should give him a tip, before Kev helped me and my big bag of Rolling Stones and Leeds United paraphernalia into his car.

‘You look like you could do with some sleep’, he astutely observed.

‘Aye, just a bit,’ I replied without going into detail. I suspected that he already knew much of the detail because he would have been in touch with Jimmy in Glasgow and in this part of Australia there wasn’t much going on so the tale of my desperate plight gave him something to talk to people about. For the first time in my life I was hot news.

He took me to a small but modern hotel which I think may have been his sister’s house because, as he introduced me to her, he told me that she worked there round the clock and he seemed to be on very friendly terms with her two young colleagues; a young boy and a young girl, both with similar facial features to everybody else except me. He led me to my room, removed the key from his pocket where it had probably been sitting for a few days and proudly introduced me to the mini bar that was heavily laden with ice cold cans of Toohey’s.

‘Get yourself off to sleep and I’ll come over around five o’clock and take you for something to eat’ he said over his shoulder as he left.

It was already something like one in the afternoon but I did what he said, luxuriating under a warm shower and lying in a soft comfortable bed for the first time in a number of days. Days that I estimated to be about three or four.

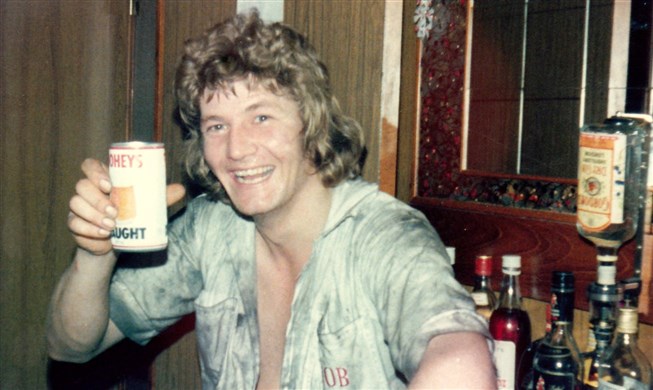

The AeroPelican passenger terminal at Newcastle Airport in New South Wales.

Kev sat down on my settee with a beer from my fridge to watch the racing results on my television. Jim in Glasgow had paid for all of these things, possibly even including the stake on Kev’s dead-cert horse that had come fifth in a race at the local track but which he unfortunately hadn’t been able to go to because he had been working; a somewhat less than subtle dig at me, I guessed.

True to his word, he had come knocking on the door of my hotel room on the stroke of five. As I was wearing fresh clean clothes and smelling less like one of his sheep shearing compatriots than I had done at our last meeting, Kev was happy to take me to his house where his wife had prepared a mixed grill for me, him, herself and their four lovely children. I could tell they were lovely children because they weren’t drinking ice cold cans of Toohey’s beer. During our meal his wife ignored all other contributors to the conversation, turning to me to conduct an intense interrogation about what the shopping was like in Leeds. She told me that her sister had once visited a place called Bolton which apparently was also in the north of England and where all the shops were rubbish apart from the butchers. Europe, for her, was the epitome of fine culture and she was desperate for more information about meat and potato pies. The kids asked me when I might be seeing them again because they only ever got sausages to eat when the people from the ships came to stay.

So when we had seen off all the sausages and all the beer and all the questions had been asked about how foggy it was in England and had I ever met the Queen or Ena Sharples, Kev announced that it was time for him to take me to the ship. It may seem strange but I was really pleased to know that I would at last be climbing up a gangway to spend the next nine months of my life afloat on twenty-odd thousand tonnes of iron and rust and coal in the company of a predominantly Scottish crew comprising of thirty-plus people who would each fit into at least one of the categories of alcoholic, pervert, stoner, psychopath or fiercely staunch Presbyterian. And I was looking upon the event as a return to normality.

As I walked towards the front gate and Kev’s car his wife gave me a peck on the cheek and the oldest of his lovely children growled, ‘Don’t forget!’

Twenty minutes later on a quayside covered with coal dust I said goodbye to Kev, thanking him profusely for his help and hospitality because my time with him and his family had been by far the best part of my incredible journey. I’ve always been very independent and able to laugh in the face of adversity but sometimes I need someone who knows what they’re doing to, figuratively speaking, hold my hand.

Suddenly the accents changed from broad Aussie to broad Scottish as half a dozen men in oil-stained boiler suits and holding cans of Tennant’s lager appeared and shook my hand, picked up my bag of Rolling Stones etc. and led me up a gangway and through a catacomb of alleyways to my cabin. Although I was more than seventeen thousand kilometres from home I at last felt like I was at home.

It’s common courtesy for navigation cadets to introduce themselves to the Captain within ten minutes of joining a ship so that they can hit the ground running in terms of being verbally abused but I was told that our ‘Old Man’ had already gone ashore and wasn’t expected back until the morning. Nudge nudge! Wink wink! So I didn’t need to bother looking for his office just yet.

Left alone, I started to unpack the Rolling Stones / Leeds United combination and a few clothes and all the books from my seat of learning (i.e. Glasgow College of Nautical Studies) that formed the basis of my seagoing correspondence course and stowed them away in seaworthy, storm-proof cupboards and drawers. But within just a few minutes the door of my cabin flew open and a dozen people who said they needed beer as a matter of urgency fell in and dragged me out for a night on the town. I didn’t really feel like I was in a party mood but I needed to make an impression and establish friendships with my latest batch of new colleagues and it wasn’t every night that we Jolly Jacks got the opportunity to let our tarred pigtails down, so I didn’t protest.

A big crowd of us going ashore was always a cause for great excitement. Such boisterous gatherings always meant that something interesting and worthy of being talked about for years afterwards was certain to happen, even though we often couldn’t remember with clarity what had really happened when discussing it the following morning. Collections of stains, cuts, bruises and beermats bearing the scribbled names and phone numbers of pretty ladies sometimes acted as physical memoranda. Our imaginations would fill in the gaps at the point of storytelling, much as mine has in the writing of this account of how things unfold when someone in a cosy city centre office sends you away all on your own to the other side of the world.

At the planning stage, a brief description of our soiree had been something along the lines of ‘just a few beers’. And that turned out to be fairly accurate for the first hour or so but the few beers led us on to a few whiskeys, which led us on to a wee drop more, which led us on to meeting a few Australians who were in the same sort of frame of mind as us and who then led us on to a spur of the moment party at the house of a woman who was a good friend of theirs out in the suburbs. It was great! Good craic, as we would say in the trade. Rum, bum and concertina, as we would say in nautical terms and which means lots of alcohol, lots of members of the opposite sex and lots of loud music, singing and dancing. The last time I had enjoyed a night out so much was the night before I had flown home from my previous ship berthed in Fremantle (near Perth, far far away on the other side of Australia) which was unbelievably similar to Newcastle and the only way you could tell the two places apart was from the fact that the people in Fremantle sign over their internal organs to the brewers of Swan lager rather than Toohey’s.

I hope my words so far have made you smile, or maybe even laugh, but I hope you’ll forgive me if you find the next few paragraphs a little less jolly.

The tale of our night ashore had what was a fairly common ending for such events. With the local police watching us in amusement, rather than the anger or fear that normal people might have expected, we arrived in taxis back at the quayside at round about 5:00 am. That wasn’t so bad really. The difficult bit was having to turn to (start work) at 8:00 am on deck supervising the local cargo handlers. In that particular port and on our company’s sort of ships (known as bulk carriers), that wasn’t too difficult as they only had to open the hydraulic covers on cathedral-size cargo hatches and tonnes of coal would be dropped in from a great height from a conveyor belt. But we also had to make sure they distributed the cargo evenly and in the correct quantities and ballast water had to be pumped out of enormous tanks to adjust the weight and strain on various parts of the ship’s hull and if we got that wrong, to put it in simple terms, it might snap in half and sink which would have caused an awful atmosphere.

For a variety of reasons, and despite the appearance of an Australian sausage sandwich and a beautiful sunrise, I wasn’t exactly feeling at my best as I stood on the deck of the ship trying very hard to look like I was still alive. I’d like to be able to say that I love the smell of coal dust, heavy oil and whiskey fumes in the morning but really the opposite was true. After about half an hour of this suffering I was approached by the Third Mate, who I had never met before. He told me that the Captain wanted to see me in his office immediately. My heart sank. I was sure I was in trouble for not going to introduce myself and/or for being an active member of a group of rowdies who might have had a drop more of the rum, bum and concertina than their brains and bodies could cope with, and on my first night on the ship too.

One sixth of half a dozen men in oil-stained boiler suits holding a can of beer. His real name was Bob but we called him Ring-pull, a nickname he earned because working in the noise of the bottom plates of a ship’s engine room where voices could never be heard, he used to gesture the opening of a ring-pull beer can to signify that it was time for us to go off for a tea break.

As we climbed the stairs to an upper deck where the Captain’s office was located, I asked the Third Mate if he knew what it was all about. As a junior officer it wouldn’t have been very long since he had been a cadet himself so I thought he might let me in on the secret but he just shook his head, avoided eye contact and looked very miserable.

The Captain introduced himself and shook my hand. He didn’t seem to be in such a bad mood at all. I thought there was a possibility that I might grow to like him.

And then he said, ‘I have a telex that I want you to read’.

I took the piece of paper and saw that it was from Jimmy in Glasgow. Perhaps I was in bother because I had bought too many cheese and pickle sandwiches in the shop at Heathrow. But it wasn’t that at all. It was much more serious. I’ll never forget those words…

CADET TERENCE MULLAN TO RETURN HOME IMMEDIATELY.

FATHER DIED SUDDENLY. MOTHER HAS NO MALE SUPPORT.

‘Go and pack your case. There’ll be a taxi here in twenty minutes and there’s a plane to Sydney in an hour’ he said. He didn’t seem to know what else to say and I was totally speechless.

Brian, the Irish Radio Officer who I’d sailed with on a previous ship, came to my cabin with a large glass of whiskey and asked me if I was alright. He said that he’d phone my mother in England later in the day to tell her I was on my way. He didn’t think it was a good idea to call her there and then because it would have been the middle of the night where she was, though I doubted that she would have been asleep.

Within four hours I had been driven to the AeroPelican Airways terminal in Newcastle, flown to the AeroPelican Airways terminal in Sydney, transferred to the international airport and was sitting on a Qantas Boeing 747 waiting to take off for London. Unlike on the outward journey, everything fell into place perfectly.

On the way to Sydney I saw again some of the people I had seen on my way out to join the ship. I had to explain to some of them why I was there but some of them already knew. They all said nice things to me. They were all so very kind.

From Sydney I was the only passenger on the jumbo jet, its emptiness making it feel even more jumbo-esque than usual. Jimmy in Glasgow and Qantas and probably a few other people in positions of authority had obviously gone right out of their way to get me back to Leeds as quickly as possible. There were only two cabin crew members. They told me that once we were up in the air I could put the armrests up on four of the seats in the middle block, lie across them and hopefully sleep. They said they wouldn’t disturb me but if I wanted anything to eat or drink I should let them know. They told me that we would be having a couple of refuelling stops but there would be nobody else getting on the plane until we got to Damascus in Syria, at which point I’d have to wake up and sit up. They were absolutely lovely.

When we arrived in Damascus the doors opened and almost all of the seats were filled up by male passengers wearing the famous all-white Arab attire and headdress. In my tee-shirt and jeans, I felt a bit conspicuous sitting amongst them. The scene must have looked like something from a Monty Python comedy sketch, especially after they had all paid their pounds to buy Qantas in-flight entertainment headphones which made them look like they were wearing stethoscopes. I never found out why there was so many of them and only one of me. The plane must have been chartered by some big Middle Eastern organisation. I think they knew why I was there though. Some of the ones sitting near to me chatted a little and others looked at me with an expression of pity on their faces. Maybe they knew that my dad had died or maybe they just felt sorry for me because I was the only one who wasn’t a millionaire oil sheikh.

Although this all happened more than forty years ago, the memory of the events up to this point remains sharp in my head; at least I think so. From Damascus onwards it’s a complete fuzz. I have absolutely no recollection of the journey from London to Leeds or of arriving home. The combined effects of the stress caused from worrying about possibly missing a plane, the stress caused by the worry of actually having missed a plane, a cumulative total of around forty-eight hours spent hanging around airports waiting for planes, two lots of jetlag, a shocking hangover, the raw emotion of unexpectedly losing my fifty-year-old father to a heart attack, having to sit through a screening of Smokey and the Bandit and drinking my own body weight in ice cold Toohey’s lager left my mind in a complete and utter mess.

As mentioned somewhere near the beginning of my story, since that difficult time in July 1978 I have never missed another plane. But sometimes I miss the life on the ships, sometimes I miss Miss Surrey, sometimes I miss the boat and sometimes I miss Australia. And I’ve often missed my father, though he’s been dead now almost as long as he was living, and time’s such a healer.

Without the kindness of the warm hearted people at Scottish Ship Management, at Qantas Airlines, and at AeroPelican Airlines together with Kev and his family in Newcastle, and without the humour of Spike Milligan and the gentlemen of Damascus, I would never have got through all this.