‘That one’s five hundred quid mate, but I could probably let you have it for four eighty,’ said the very gaunt looking man pointing to the clock that looked a lot like the one you’d see on a box of Rowntree’s After Eight Mints.

In such circumstances I wonder why market traders so often offer a reduced price without there having been even a faint suggestion of haggling. Why don’t they just mark their acceptable price on the item for sale in the first place? And even if I had been going to haggle with him, I would have been expecting to settle at something way below what he had already considered to be a bargain. This never happens in Lidl; well not without a yellow sticker on a tub of yoghurt the day before it turns to penicillin.

Wouldn’t it be grand if lovely Desislava who works on the checkout at our local supermarket were to say, ‘That comes to eighty-two leva and sixteen stotinki, sir, but the shopping’s yours for seventy leva and that’s my final price.’? My dear Priyatelka, who is French but has contracted a bit of my Yorkshire-ness since we met, would then offer fifty.

‘I wasn’t looking to buy one. I just wondered if you knew anybody who can repair old clocks,’ I replied to the purveyor of second-hand clocks, several specimens of which included second-hand second hands. I already had one at home that was in bad shape but it had been known to majestically command a place on the old oak sideboard in my Nan and Grandad’s house since what seemed like the beginning of time; but it must have been later than that because surely only the very astute would have had a need for a clock on the very day that the concept of time was introduced to the world.

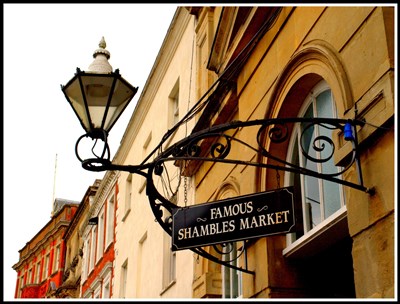

He told me that he could fix them himself but obviously not on a trestle table in the draughty corridors of the Shambles antique market in Devizes. The name on his business card (not cards … he only had one to give away) was Joseph Antram but he told me to call him Joe and said he would need to come to my house to see the clock and give me his verdict. He wrote down my mobile phone number and promised that he would ring me soon to arrange a date for a visit.

The Shambles antique market in Devizes.

Several days passed and I heard nothing from him. Having reached a point that was way past the anticipated ‘soon’, I thought that perhaps his clock wasn’t working and he had lost all track of time. I thought that perhaps he’d sold one of his antique timepieces and gone on holiday with the proceeds but, given the astronomical retail prices he was recommending, that was unlikely.

The next Sunday, before it was even light, my phone rang and it was him. His clock really must have been broken because no one in their right mind would want to talk business at such an uncivilised hour. He must have realised his mistake and, eager to return to his bed, we quickly agreed that we would meet at my front door at eleven o’clock that very morning.

Just after twelve the doorbell rang. He apologised for being late, explaining that he had run out of petrol because the fuel gauge on his car was a bit dodgy. While he was talking he looked at the clock that I had taken down from its dusty home on top of my bookshelf and placed on the kitchen table.

After a minute or two he sighed and said, ‘Poor old thing has certainly seen better days.’ Words which, I felt, could have been used to describe adequately both himself and his car.

I explained that I could remember the clock working when I was a kid but years of abuse and neglect had left it in this sorry state.

‘How can you abuse a clock?’ Joe asked.

‘Well, me and my friend Gavin used to open the back and give the pendulum a bit of a shove to make it swing faster so that it would chime the hour a bit sooner but our theory didn’t seem to work and, shortly afterwards, neither did the clock. And then there was my Grandad,’ I told him.

‘Your Grandad?’

‘Yes. He had been very ill for a long time before he died but tried to continue in his role as chief clock winder-upper even though he was no longer sure what to do. So there would have been quite a lot of over-winding of the spring and twisting of the hands in all directions but clockwise,’ I added.

‘That’s a shame,’ he said, scratching his chin. ‘It’s a lovely clock.’

‘How much do you think it’s worth?’ I asked in my best Antiques Roadshow voice.

His reply was, ‘Well if it was working, about fifty quid.’

‘And how much would it cost to repair?’

‘About fifty quid,’ he said, as I made a mental profit and loss assessment of the situation.

The clock, although nice to look at and a bit old, can’t really be described as either beautiful or antique. It doesn’t even have a cuckoo. It dates back to the 1930s when German manufacturers flooded the British market for wooden, wind-up, striking clocks. He told me that back then just about every respectable council house occupying family owned one as a symbol of having moved up in status from the squalor of life in the inner city slums. This is why such a clock was never seen in any of the Dick Van Dyke scenes in the film Mary Poppins. Sadly, their popularity tailed off at a rate conversely proportionate to that of air-raid shelters round about September 1939.

Weighing up the circumstances, I decided that I would give Joe the job of fixing the old ticker. Fifty pounds wasn’t a vast amount of money and I was sure it would cost me more than that to buy a decent new clock in a shop in the High Street. It could have been so much more. In fact, it was round about what I would normally have spent in a month on phone calls to the speaking clock telephone service. I must confess that I was more prone to dial that number during my hours of loneliness just to hear the soothing voice of the lovely lady who always knew what the time would be at the third stroke than I was to merely discover the time.

‘I’ll give you a call in a few days when I’ve got it working,’ Joe remarked cheerfully as he carried the tired old timepiece out to his car.

At that stage I was pleased with the progress but a few days later he hadn’t rung me. A couple of weeks later there was still no news. So I called him but there was no answer. I called him another four or five times over the course of the next couple of days, but still no answer. I dialled up the speaking clock lady who made my heart skip a beat as she advised me that after the third stroke it would be six fifty-two and thirty seconds, but she had no news about Joe and my clock. She may have been the original good time girl but she was hopeless when it came to providing any other sort of information.

My dear old clock at five past ten this morning.

I decided that I would sit tight and wait patiently for Joe to contact me. It had been almost fifty years since I had last seen the clock working so I was in no rush. But the weeks went by and I completely forgot about it. I couldn’t even say roughly how many weeks it had been because in those days I was a high-flying self-employed businessman so I didn’t have the time to sit around looking at clocks.

And then one day, out of the blue, my phone rang.

‘I’m really sorry. I’ve had your clock for nearly four months,’ said the voice at the other end of the line, which was obviously Joe’s. ‘I’m just recovering from my second major heart operation and I’ve been trying to sort out the broken clocks of the crowd of foul-mouthed irate people who have been ringing me up every day to ask where their broken clocks are.’

‘So where is my clock?’ I asked politely, not wanting to be part of the crowd.

‘It’s here, in front of me,’ Joe responded without hesitation.

‘Is it working?’

‘No!’ Again no hesitation.

‘When might it be working?’ I further enquired.

‘Well provided that there’s no leaking from the valves I should be able to let you have it back at the weekend,’ said Joe.

‘I didn’t know clocks had valves,’ I remarked, thinking that he was winding me up.

‘They don’t,’ he replied. ‘I mean the valves in my heart that have just been operated on. The stitches might still be a bit fragile.’

I told him that it would be nice to be reunited with my chronometer but not to put himself under any pressure on my behalf. I could just imagine the headline on the front page of the local paper KILLER CLOCK STRIKES AGAIN and the remorse that would torment my mind forever.

True to his word, Joe the clock repairer, looking very much on the alive side, arrived at my house to demonstrate the tick-tocking and dong-donging that I hadn’t heard for such a long, long time. Proudly, he accepted his fee of fifty pounds plus another fiver that I gave him out of guilt at not having taken him flowers, grapes and Lucozade while he was in hospital.

Ten years later the clock is still going strong. It has reclaimed its place on top of the same bookshelf on which it sat back in the days when I lived in England though now, three thousand kilometres away at the other side of Europe, it has a completely new layer of dust. It looks great and the lovely sound of its mechanism adds such a lot to the homely atmosphere of our relatively new Bulgarian abode. It can’t be relied upon if I have a specific deadline for catching a bus or even if I am trying to boil an egg but despite this I love it, and the memories it conjures, to bits. The catch on the glass door that covers the clock face is a bit worn so sometimes it springs open of its own accord. If this happens while I’m sitting alone with a book at night, the shock is almost enough to give me a heart attack.

After a busy introduction to the world, the dear old clock had a long period of being inoperative, followed by the trauma of undergoing major repairs but now enjoys a sedate life just ticking away at its leisure. It is my heartfelt wish that these same words can be used to describe the way that things have panned out for Joe in Devizes.