Each day, as the factory whistle blew at noon, he dashed leisurely home from work on his bicycle to have his dinner because dinner was always eaten at dinnertime and, like most of the twenty-odd thousand other people who worked at the Rowntree’s factory in York in the 1960s, he didn’t have a car. Britain, apparently, had never had it so good so staff canteens, plastic sandwich boxes and cartons of yoghurt had been introduced to society but they were all a bit out of my Grandad’s price range and perhaps considered a bit pretentious; a word that my Grandad never used because even using the word ‘pretentious’ seemed a bit pretentious; and ‘poncey’ hadn’t yet been invented. His insistence that my Nan adhered to her strict daily schedule for serving midday meat and two veg, and usually a pudding too, ensured that his only business expenses were what he needed to buy an annual puncture repair kit and to replace his weather beaten cloth cap with one made from a lighter material at the start of every third or fourth summer. The term ‘tax deductible’ was something that he never encountered in his modest way of life, as were Tupperware and fromage frais. Pedalling back to work with a belly full of good honest northern working class cuisine was something that he encountered every afternoon from Monday to Friday.

I could never understand why he needed to come home for his dinner. His workplace was a sea of KitKats, Smarties and After Eight mints. Were they not the ingredients of the ultimate feast for any mortal being? To this day, Fruit Gums remain an integral part of my diet and, should I ever find myself sentenced to death and be asked what I would like for my final meal before facing the firing squad, I would go for a packet of Jelly Tots every time. I could only think that he made this mile-long round trip bike ride to burn off the calories from the boxes of Black Magic he had no doubt scoffed during the course of his morning’s work. For me, he had the perfect job and I knew that when I grew up I didn’t want to be a train driver, a spaceman or the centre forward at Melchester Rovers; I wanted to be the man who put the bubbles in bars of Aero.

In November 1964 disaster struck. My Grandad, a nineteenth century boy by the skin of his dentures, reached the ripe old age of sixty-five and the sons of Joseph Rowntree decided that after more than forty years of service it was time for him to retire from the place that the local people fondly referred to as the Cocoa Works. Looking back at the day when he hung up his cycle clips for the final time, I suspect he was quite pleased about the change in his daily routine but all I could think about was where we would get our free confectionery from then on. Luckily his retirement package included a lifetime’s supply of misshapes (known in the trade as ‘waste’) bodged up by his former colleagues who were still working. There was even a widow’s waste allowance in the event of him predeceasing my Nan, so right up to my late teens I can remember our family’s Saturday night entertainment comprising mostly of us trying to separate a slab of fifty Midnight Truffles or Coffee Crescents that had been drowned and stuck together in an ocean of dark chocolate as a result of a malfunction with a conveyor belt and / or an operator’s hairnet. On Monday mornings at school my friends would ask me if I had watched that week’s episode of Kojak or Starsky & Hutch but I always had to confess that in our house we had all been far too sticky to be able to turn the television on.

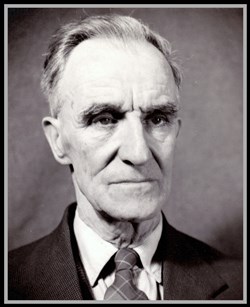

I was too young to understand retirement so I asked my parents why Grandad didn’t go to work anymore and I was told that it was because he was old. I couldn’t understand this either because he had never looked anything other than old to me. He was a lean and quiet man with a lined face that looked to be full of worry and eyes set in deep sockets exaggerated by thick dark eyebrows. He dressed in the way that he had always dressed, limited by a lifetime of shortages in terms of both the styles available and the money required to buy them. He was the seventh son of a seventh son which, even in the days of large families, was a rare phenomenon and said to bring good luck, though it didn’t appear to have done so in his case. Active service in World War One, struggling to stay in employment during the Great Depression, having a young family under his wing during the dark days of World War Two, the shock of his adult son’s premature death and the rigours of his decades of manual work on the factory floor certainly had wearied him. So why hadn’t he retired sooner? If he had been around in more recent years I’m sure he would have been given the opportunity to do so. I suppose a reduced income was the disincentive.

As far as I can remember he enjoyed his retirement, using his newfound spare time to engage in many of the things that he had wanted to do but had been restricted by work commitments. Coach holidays to Great Yarmouth and Ilfracombe with my Nan, talking to Fred the next door neighbour about his racing pigeons, going for a pint and a game of dominoes at his local pub (the Shoulder of Mutton), smoking cigarettes and talking a little to me when I was there during school holidays.

He never told me but he must have always had dreams of a more extravagant lifestyle. On Saturday afternoons at five o’clock we would have to watch the football results on Grandstand on the BBC, which was the ultimate in tedium to me at the time.

‘Why are we watching this, Grandad?’ I would ask.

‘To see if we’ve won a million pounds’ was his standard reply.

But the results that I heard were things like ‘Arsenal nil Leeds United four’ without there ever being any reference to Harry Taylor, or anybody in the world for that matter, winning a million pounds. However, I was glad that I had been able to accompany him in his world of sport. It was another ten years before I understood the meaning and significance of getting eight score draws on Littlewoods Pools but I had nobody with whom I could share the pain of the classified results and the realisation of having to face at least another week of life’s mediocrities. I really could have done with him being there, even if it was only to comfort me with a Lion Bar.

My Grandad, Harry Taylor.

I think I can probably remember everything he said to me as a kid because he rarely said much at all. Talking was somewhere way down the list of his daily activities but he always had a few words to say when he saw me struggling to reach up for something that was just out of my grasp.

‘You want to get some horse muck in your boots’ he would remark with regard to my height and I would laugh every time.

One day his shaving mug containing razor, brush and soap had been pushed back a little further than usual on the shelf above the kitchen sink.

As he stretched to get the tips of his fingers to it, I said to him, ‘You want to get some horse muck in your boots Grandad’, pleased with myself that I had been able to get him with his own clever comment.

But he had me straight back in my place with ‘I put some horse muck in my boots but now I’ve just got bigger feet’.

I spent part of my childhood living in a small town in Ireland with my parents and sister. My Nan and Grandad loved visiting us there. It meant going on a ferry to cross the wild and stormy Irish Sea which, to them in the 1960s, was considered to be a long haul journey of intrepid proportions. They would stay with us for weeks but although my Nan kept herself occupied by helping my mother drink cups of tea and talk to the neighbours, my Grandad would sometimes find himself at a bit of a loose end. So he would take our dog for a walk. He was usually gone for hours and we assumed the two of them were exploring the nearby fields and open countryside. When they arrived home they both seemed tired but the old fella more so than the dog.

One summer our elderly Uncle George came to visit us and he too offered to take the dog for a walk. He too was gone for two or three hours and when he returned he admitted that he had been for a pint in the Northern Star, one of the pubs in the Diamond (Irish market place). He said that he had been a little hesitant to do so as he, with his north east England accent, felt quite a stranger in a town where he was sure everybody would have strong rural Irish accents and he was concerned about the reception he would get. As he entered the public bar no one really noticed him but most of the customers made a big fuss of the dog who seemed unexpectedly excited to see them.

‘How come everybody knows the dog?’ George enquired.

‘Oh, when Harry’s over from England on his holidays he comes in here regularly with him’ the barman replied. ‘He’s called Bruce and he loves cheese and onion crisps!’ George was already aware of this dietary preference because before the head had settled on his pint Bruce was on his second packet of Tayto’s … on the house, of course!

Of all Harry’s pastimes it’s the smoking that remains the most vivid in my mind. While he had been working he had smoked Embassy Regal. I used to count up the coupons he collected from the packets and pore over the Embassy gift catalogue to see what we might exchange them for. My materialistic eye would be caught by bathroom scales, guitars, coffee percolators and dartboards, all of which had up to then been considered unobtainable luxuries in our family but now that we were coupon-rich I could sense that things were about to change.

I asked him once what he was saving his coupons for and he replied ‘An iron lung!’ I scanned the index and found electric irons on page 136 but there was no sign of the object of his desires. I assumed that it was some innovative piece of machinery for making delectable chocolate comestibles, asked no further questions and hoped that I might be the owner of one myself one day.

In retirement he had the time to sit back and relax and smoke in style. He converted to Golden Virginia tobacco and rolled his own wispy little suggestions of cigarettes; mere shadows of the proud and firm Embassy Regal to which we had become accustomed. They seemed a bit pointless to me and I wondered if they were doing him any good. Packets of rolling tobacco didn’t contain the coupons so we never did see that iron lung that we had had our hearts set on. As his health deteriorated he was given a device known as a hand rolling machine which did a much better job than his shaky fingers alone had ever done. This was my first experience of assistive devices for the elderly and I was intrigued. He would sometimes let me have a go at making a rollie, which was good training for when he became too ill to make them himself.

‘Do us a cig, our Terry’, he would say. Delighted to be able to make life easier for him I would grab the little metal contraption, line it with a Rizzla paper, neatly place a filter at one end and then ram in as much tobacco as my little hands could manage before finishing off with the rolling action and a dribble of saliva to seal the contents in. I was so proud of the results of my handiwork as they usually appeared cylindrical and sturdy, just like the ones he used to buy in the shops.

The problem arose when he tried to light one of these creations. They were solid tobacco throughout and probably more like a cigar than a cigarette. Consequently, it was difficult to draw air through them with his aged lungs. The fact that his false teeth were rarely in the same room, let alone attached to his gums, made the situation worse as the insides of his cheeks met in the centre of his mouth so that he looked as though he might suck his brain out of place when he tried his damnedest to inhale the nicotine. I was worried that this would make him ill, or even finish him off, so I used to light them myself and pass them to him.

Not long after his seventieth birthday, something else finished him off. His health was failing so much that even our scant conversations dried up, though I would sit with him to keep him company. His friend, Mr Wilson, would sit with him too but, because he was a similar sort of character to my grandfather, the only thing I ever knew about him was that he was called Mr Wilson.

After my Grandad died I never put another cigarette to my lips and I’ve never visited Great Yarmouth or Ilfracombe. Something else I never did was to ask him enough questions. I never knew about what he saw in Flanders in 1918. I never asked him what he saw in pigeon racing. I never found out how many Cocoa Works employees it took to make a Polo mint. I never knew if he enjoyed the Guinness in the Northern Star … I would have loved to have had a pint or two with him. I never knew very much about his life at all but what I do know, I will always remember.